Through stories of extraordinary courage, like a young boy training for the Paralympics, Emma and host Cheryl explore what it truly means to live a Bodhisattva vow, to act with skillful compassion, and to stretch beyond one’s comfort zone in the service of others.

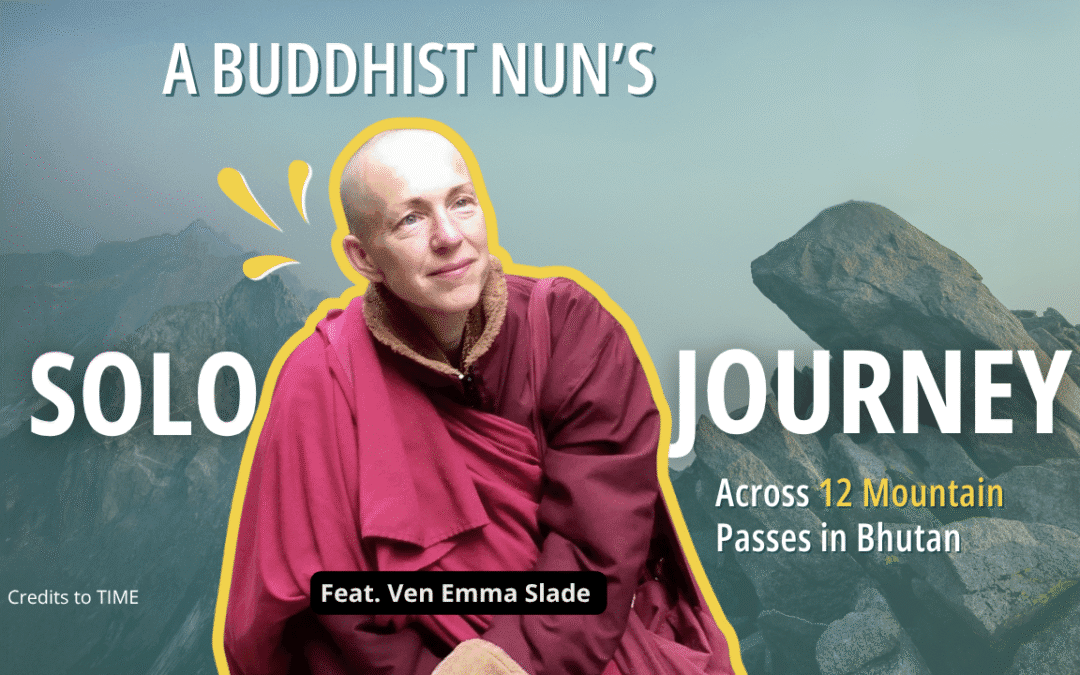

👤 Lopen Ani Pema Deki (Emma Slade) was born in Kent, and was educated at Cambridge University and the University of London where she gained a First Class degree. She is a qualified Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) and worked in Fund Management in London, New York, and Hong Kong.

A deep seated desire to enquire into the deeper aspects of humanity arise following a life- changing business trip to Jakarta, where she was held hostage at gunpoint. She resigned from her financial career and began exploring yoga and meditation and methods of wellbeing with the ultimate aim of turning a traumatic episode into wisdom and conditions for thriving.

She qualified as a British Wheel of Yoga teacher in 2003 and, over the last 19 years, has run numerous yoga workshops and retreats. Her interest in Buddhism as a science of the mind strengthened after meeting a Buddhist Lama (teacher) on her first visit to Bhutan in 2011. This crucial chance meeting led to her studying Buddhism with this Lama and, eventually, led to her becoming the first and only Western woman to be ordained in the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan as a Buddhist nun.

Emma shows how real compassion isn’t passive — it asks us to stretch, act, and often suffer discomfort to truly benefit others.

From Bhutanese communities to a child training for the Paralympics, Emma shares how positivity and resilience can transform suffering into strength.

In helping others, empathy and timing are crucial. Emma explains how “checking the cup” — seeing if someone’s mind is open — ensures that compassion lands without harm.

Full Transcript

[00:00:00] Emma Slade: We can’t expect ourselves to act as if we’re enlightened beings when we are not yet. Like we drive a Ferrari when we are only capable of riding a bike.

[00:00:09] Emma Slade: It’s just a bonkers expectation.

[00:00:11] Cheryl: If you think you’re not suffering, think again.

[00:00:14] Cheryl: Welcome to the Handful of Leaves Podcast. My name is Cheryl, and today I’m joined by Emma Slade also known as Ani Pema Deki.

[00:00:22] Cheryl: Emma Slade is a Buddhist nun, author and founder of Opening Your Heart to Bhutan, a charity supporting hundreds of children with special needs. She’s now preparing to walk the

[00:00:32] Cheryl: Wild Bhutan Trail, 37 days solo across mountains and valleys to raise funds for these children who inspire her resilience.

[00:00:41] Cheryl: Let’s begin.

[00:00:47] Cheryl: Can you share with us more about your work with the special needs children there?

[00:00:50] Emma Slade: So I set up my UK registered charity Opening Your Heart to Bhutan 10 years ago. And that was very linked to my practice and my integrity as a Buddhist monastic, because I’d mainly studied the teachings and selflessness of compassion.

[00:01:05] Emma Slade: And then certain circumstances arose in Bhutan and really propelled me to help children with special needs in Bhutan or in very difficult circumstances. And it did feel like, okay, you studied all this compassion and you developed.

[00:01:20] Emma Slade: So it felt definitely directly related to my practice. So we’ve helped hundreds of children now in Bhutan. We’ve played a big part in building the first purpose-built special needs school. I was doing this walk across Bhutan for 37 days, to hopefully raise a big amount of money to secure the future of the school and the children in it. It’s 37 days, 12 mountain passes, 6 climate zones, and 403 kilometers.

[00:01:48] Emma Slade: And then after that I’m not, I’m not walking anywhere after that.

[00:01:51] Cheryl: What were some stories making you have such affinity with special needs children?

[00:01:59] Emma Slade: As you know, I was held hostage in that hotel room in Jakarta. And when I was held hostage, I felt so physically trapped and so unable to have any autonomy about my body.

[00:02:11] Emma Slade: And so I think when I encountered a girl in Southern Bhutan 11 years ago or whatever it was, the feeling of the lack of autonomy had a big impact on me.

[00:02:23] Emma Slade: I could empathize, it’s just very humbling to be around children like that. I’ve been very lucky with my opportunities, my skills that seem to be… have come quite easily to me in this life, right?

[00:02:36] Emma Slade: And so when things come easily to us, we tend to not see them very clearly. We don’t think, oh wow, I’ve managed to walk or cross the kitchen to get a cup of coffee. Some of these children that I spend time with, to walk across the kitchen to make a coffee is a big achievement and requires huge patience, requires huge determination. I just have so much admiration for their achievements. They don’t give up. I think I would just go, oh, this is just too hard. I would give up. So there’s something about that that I find very moving and it makes me want to support them. Want to help them achieve things, help them have a meaningful life.

[00:03:16] Cheryl: Would you like to share also one of the achievements that really touches your heart till today?

[00:03:21] Emma Slade: We had a boy in the Eastern school who had a physical condition, which meant he walked on his knees. Just think about that for a moment.

[00:03:29] Emma Slade: We looked into, could we give him some operation? It’s very complicated because a lot of the medical solutions, they would cause other problems. Anyway, he was the most positive charge you’re ever gonna meet. He played cricket on his knees, he was like batting, he would play football on his knees. And somebody came to visit the school, and they were just completely inspired by him. And so they did lots of little videos about him, and the Paralympics people picked it up in Bhutan.

[00:03:58] Emma Slade: And he is now training for the Paralympics to represent Bhutan. His spirit was absolutely incredible. I think most people would just give up on life and be completely depressed, and he was the most enthusiastic, positive, positive child. And now this great opportunity has come his way.

[00:04:17] Cheryl: It makes me so happy to hear that.

[00:04:19] Emma Slade: It just shows you the power of your mindset. His mental suffering, his attitude to his physical suffering could have been just so negative, but due to his response to his physical situation, it was incredible. It’s a big Buddhist teaching right there.

[00:04:36] Cheryl: Absolutely. Yeah. And I recall in our past conversation, we were talking about what do you think make Bhutanese people happy? And you mentioned it was their resilience.

[00:04:47] Emma Slade: Yeah. They are very resilient, very resilient people. They stick together and they support each other when things get tough. And I think that’s part of their resilience as individuals, but also as communities, when things get tough, they really pull together. I think that’s very interesting.

[00:05:05] Cheryl: In the 11 years where you’re working on this school, was there a moment where you felt like actually wanting to give up?

[00:05:14] Emma Slade: Oh, yeah. Many moments. Many moments because we talk about Bodhisattva vows and helping others and what you’re doing when you deliberately try to help others is you’re moving out of a comfort zone. It’s very comfortable just to think about yourself or a couple of people, right? When you deliberately decide to expand that and help others, it’s not going to be easy, and it requires a determination to keep going. It’s much easier just to shrink back and just think about yourself. So yeah, there were many moments because it’s exhausting. Especially fundraising, and it’s very awkward as a person, somebody in monastics, you feel like you’re going, oh, please. Can you give a charity some money? That’s kind of awkward in robes, right? So there’ve been many moments, but I’m really pleased I’ve continued and I can’t really believe what we’ve achieved now, and I’m so grateful that so many people have been inspired by what I’ve done, and they have wanted to support me because if they hadn’t, then I wouldn’t have been able to do all of this.

[00:06:08] Emma Slade: It’s been a big job, but when you help others, when you expand that space of your mind, you can rest easy. A lot of mental peacefulness doesn’t just come from meditating or something.

[00:06:20] Emma Slade: It has a great benefit to the mind from broadening it with compassion.

[00:06:25] Cheryl: I have two questions. When it gets really hard, what is one thing that motivates you to keep going in terms of the charity? And secondly, what motivates you to keep holding onto the Bodhisattva vow?

[00:06:37] Emma Slade: Generally, walking a Buddhist path with all its practices and obstacles and integrity, you know, it is not easy. The other day I was going up a mountain in Bhutan to find my teacher who was quite high up in a mountain in Bhutan and it was so hot and the mountain was so steep and I was trying to get there on time and my legs were really feeling it.

[00:07:02] Emma Slade: And then you just have to remember all the tales of the Tibetan masters, like Milarepa had to do so many things to find their teacher, had to travel so far to gain teachings, etc. So I think generally in the Himalayan Buddhism, which I know the most about. You’ll see that lots of true practitioners actually had to struggle and work with a lot of determination to follow their path.

[00:07:27] Emma Slade: And your second question was not to give up on the Bodhisattva vow. So when we look at the Bodhisattva vow, we have the aspiration to help all beings and achieve enlightenment for the benefit of all beings. Now, there’s nothing to stop your mind wishing that all the time, there’s no obstacle to it other than your own mental poisons, self clinging, distraction, worldly activity, etc.

[00:07:51] Emma Slade: The aspiration. You can never lose as long as you pay a bit of attention to it. Putting that into action is the tricky bit, but as long, even if you are in a stage where it’s hard to apply it, you just draw back and recall that aspiration. So the mind is never losing that connection with the wish to become a Bodhisattva.

[00:08:12] Emma Slade: We take our refuge and Bodhicitta vow every day. And so I think repeating those words, hearing your own voice, say those words out loud, echoing back into your consciousness, that’s important if you want to keep going at it.

[00:00:00] Emma Slade: We can’t expect ourselves to act as if we’re enlightened beings when we are not yet. Like we drive a Ferrari when we are only capable of riding a bike. It’s just a bonkers expectation.

[00:00:11] Cheryl: If you think you’re not suffering, think again.

[00:00:14] Cheryl: Welcome to the Handful of Leaves Podcast. My name is Cheryl, and today I’m joined by Emma Slade also known as Ani Pema Deki.

[00:00:22] Cheryl: Emma Slade is a Buddhist nun, author and founder of Opening Your Heart to Bhutan, a charity supporting hundreds of children with special needs. She’s now preparing to walk the Wild Bhutan Trail, 37 days solo across mountains and valleys to raise funds for these children who inspire her resilience.

[00:00:41] Cheryl: Let’s begin.

[00:00:47] Cheryl: Can you share with us more about your work with the special needs children there?

[00:00:50] Emma Slade: So I set up my UK registered charity Opening Your Heart to Bhutan 10 years ago. And that was very linked to my practice and my integrity as a Buddhist monastic, because I’d mainly studied the teachings and selflessness of compassion.

[00:01:05] Emma Slade: And then certain circumstances arose in Bhutan and really propelled me to help children with special needs in Bhutan or in very difficult circumstances. And it did feel like, okay, you studied all this compassion and you developed. So it felt definitely directly related to my practice.

[00:01:24] Emma Slade: So we’ve helped hundreds of children now in Bhutan. We’ve played a big part in building the first purpose-built special needs school. I was doing this walk across Bhutan for 37 days, to hopefully raise a big amount of money to secure the future of the school and the children in it. It’s 37 days, 12 mountain passes, 6 climate zones, and 403 kilometers. And then after that i’m not, I’m not walking anywhere after that.

[00:01:51] Cheryl: What were some stories making you have such affinity with special needs children?

[00:01:59] Emma Slade: As you know, I was held hostage in that hotel room in Jakarta. And when I was held hostage, I felt so physically trapped and so unable to have any autonomy about my body. And so I think when I encountered a girl in Southern Bhutan 11 years ago or whatever it was, the feeling of the lack of autonomy had a big impact on me.

[00:02:23] Emma Slade: I could empathize, it’s just very humbling to be around children like that. I’ve been very lucky with my opportunities, my skills that seem to be… have come quite easily to me in this life, right?

[00:02:36] Emma Slade: And so when things come easily to us, we tend to not see them very clearly. We don’t think, oh wow, I’ve managed to walk or cross the kitchen to get a cup of coffee. Some of these children that I spend time with, to walk across the kitchen to make a coffee is a big achievement and requires huge patience, requires huge determination. I just have so much admiration for their achievements. They don’t give up. I think I would just go, oh, this is just too hard. I would give up. So there’s something about that that I find very moving and it makes me want to support them. Want to help them achieve things, help them have a meaningful life.

[00:03:16] Cheryl: Would you like to share also one of the achievements that really touches your heart till today?

[00:03:21] Emma Slade: We had a boy in the Eastern school who had a physical condition, which meant he walked on his knees. Just think about that for a moment.

[00:03:29] Emma Slade: We looked into, could we give him some operation? It’s very complicated because a lot of the medical solutions, they would cause other problems. Anyway, he was the most positive charge you’re ever gonna meet. He played cricket on his knees, he was like batting, he would play football on his knees. And somebody came to visit the school, and they were just completely inspired by him. And so they did lots of little videos about him, and the Paralympics people picked it up in Bhutan.

[00:03:58] Emma Slade: And he is now training for the Paralympics to represent Bhutan. His spirit was absolutely incredible. I think most people would just give up on life and be completely depressed, and he was the most enthusiastic, positive, positive child. And now this great opportunity has come his way.

[00:04:17] Cheryl: It makes me so happy to hear that.

[00:04:19] Emma Slade: It just shows you the power of your mindset. His mental suffering, his attitude to his physical suffering could have been just so negative, but due to his response to his physical situation, it was incredible. It’s a big Buddhist teaching right there.

[00:04:36] Cheryl: Absolutely. Yeah. And I recall in our past conversation, we were talking about what do you think make Bhutanese people happy? And you mentioned it was their resilience.

[00:04:47] Emma Slade: Yeah. They are very resilient, very resilient people. They stick together and they support each other when things get tough. And I think that’s part of their resilience as individuals, but also as communities, when things get tough, they really pull together. I think that’s very interesting.

[00:05:05] Cheryl: In the 11 years where you’re working on this school, was there a moment where you felt like actually wanting to give up?

[00:05:14] Emma Slade: Oh, yeah. Many moments. Many moments because we talk about Bodhisattva vows and helping others and what you’re doing when you deliberately try to help others is you’re moving out of a comfort zone. It’s very comfortable just to think about yourself or a couple of people, right? When you deliberately decide to expand that and help others, it’s not going to be easy, and it requires a determination to keep going. It’s much easier just to shrink back and just think about yourself. So yeah, there were many moments because it’s exhausting.

[00:05:42] Emma Slade: Especially fundraising, and it’s very awkward as a person, somebody in monastics, you feel like you’re going, oh, please. Can you give a charity some money? That’s kind of awkward in robes, right? So there’ve been many moments, but I’m really pleased I’ve continued and I can’t really believe what we’ve achieved now, and I’m so grateful that so many people have been inspired by what I’ve done, and they have wanted to support me because if they hadn’t, then I wouldn’t have been able to do all of this.

[00:06:08] Emma Slade: It’s been a big job, but when you help others, when you expand that space of your mind, you can rest easy. A lot of mental peacefulness doesn’t just come from meditating or something. It has a great benefit to the mind from broadening it with compassion.

[00:06:25] Cheryl: I have two questions. When it gets really hard, what is one thing that motivates you to keep going in terms of the charity?

[00:06:32] Cheryl: And secondly, what motivates you to keep holding onto the Bodhisattva vow?

[00:06:37] Emma Slade: Generally, walking a Buddhist path with all its practices and obstacles and integrity, you know, it is not easy. The other day I was going up a mountain in Bhutan to find my teacher who was quite high up in a mountain in Bhutan and it was so hot and the mountain was so steep and I was trying to get there on time and my legs were really feeling it. And then you just have to remember all the tales of the Tibetan masters, like Milarepa had to do so many things to find their teacher, had to travel so far to gain teachings, etc.

[00:07:14] Emma Slade: So I think generally in the Himalayan Buddhism, which I know the most about. You’ll see that lots of true practitioners actually had to struggle and work with a lot of determination to follow their path.

[00:07:27] Emma Slade: And your second question was not to give up on the Bodhisattva vow. So when we look at the Bodhisattva vow, we have the aspiration to help all beings and achieve enlightenment for the benefit of all beings. Now, there’s nothing to stop your mind wishing that all the time, there’s no obstacle to it other than your own mental poisons, self clinging, distraction, worldly activity, etc.

[00:07:51] Emma Slade: The aspiration. You can never lose as long as you pay a bit of attention to it. Putting that into action is the tricky bit, but as long, even if you are in a stage where it’s hard to apply it, you just draw back and recall that aspiration. So the mind is never losing that connection with the wish to become a Bodhisattva.

[00:08:12] Emma Slade: We take our refuge and Bodhicitta vow every day. And so I think repeating those words, hearing your own voice, say those words out loud, echoing back into your consciousness, that’s important if you want to keep going at it.

[00:08:30] Cheryl: Thank you so much for sharing. And it, I think it’s really true that the challenge is really in turning it into action. And for me personally, sometimes I feel, oh, it’s so hard to help people. They don’t wanna be helped.

[00:08:47] Cheryl: And a lot of determination comes in to continue.

[00:08:50] Emma Slade: What would be a situation where you found that?

[00:08:55] Cheryl: So for example, with helping a sibling, where they’re very stuck in unwholesome actions that are unbeneficial for them and having to choose kindness over temper. And having to do that again and again so that I can plant the seeds of wholesomeness.

[00:09:11] Emma Slade: I would say that one has to be skillful with seeing the situation clearly. So if there’s a sibling or whatever who actually really doesn’t want to be dragged towards virtuous activity, and it might even create more resentment between the two people, then one has to be skillful and realize, okay, this is not the right moment, or this is not the right way of saying it.

[00:09:34] Emma Slade: You can always have the prayers, the aspirations for them. But I think it’s usually best to treat another adult as an adult. And if you kind of take the role of telling them what to do and this is best and they’re doing it wrong, people’s threat mechanism in the back part of their brain will be alerted and you’ll become an enemy to them.

[00:09:53] Emma Slade: They’ll get defensive and then they won’t hear. They just literally will go like, like this. Right. So you know, when we talk about skillful means as well as wisdom, when it comes to sharing the Dharma, wishing to help others, we have to be skillful in how we do that.

[00:10:10] Cheryl: Can you share more about what it means to be skillful?

[00:10:12] Emma Slade: So you have to listen well. Use your empathy. Are you pushing something on somebody that they don’t want to hear it? And it might create conflict and disharmony between you.

[00:10:23] Emma Slade: In Buddhist text, we’ll see this example of seeing whether the mind is like an open cup. Open to receiving teachings, whether it’s a cup with a hole at the bottom, so the teachings just go right through. Or whether it’s a cup that’s closed, so nothing’s gonna go in. So I think it’s useful to, when we think about skillfully communicating with others around the Dharma just to see, okay, what kind of cup am I looking at here?

[00:10:49] Cheryl: Oh, that’s a powerful analogy. Always checking to see what’s the status of the cup right now.

[00:10:54] Emma Slade: And they’re not blaming the person for whatever reason the cup is still like this right now. And then also it’s a waste of your energy and time. Also for yourself, are you the kind of student that attends lots of teachings, but then two weeks later you can’t remember anything? It just went through you. So it’s also useful for your own reflections.

[00:11:12] Cheryl: Yeah. Yeah, A lot of times, it all starts from a good place, but when it’s mixed with not the skillful way of executing or doing it, then sometimes the results are, are not good as well.

[00:11:26] Emma Slade: There’s two ways of looking at that from a karmic point of view. If the intention is really clean and pure, then that’s the most important thing, right? We can have a very good intention. And then that intention, comes into the interconnected web of suffering, which is samsara, and it kind of goes a bit wrong. But Buddhism really emphasizes to keep with those clean intentions, keep coming back to them.

[00:11:50] Emma Slade: Until we are enlightened, it may be a bit messy in the application. We have to recognize where we are right now and be understanding of that. And so it’s always worth thinking, “Compared to a year ago, am I dealing with this person more skillfully than a year back?”

[00:12:07] Emma Slade: “I may not be dealing with them perfectly, but is, is it going in the right direction?”

[00:12:12] Emma Slade: We can’t expect ourselves to act as if we’re enlightened beings when we are not yet. Like we drive a Ferrari when we are only capable of riding a bike. It’s just a bonkers expectation, tempting as it is. So we have to see clearly the situation, but also our own situation, our mind now.

[00:12:32] Cheryl: I love that analogy.

[00:12:35] Emma Slade: Reality is such an important place. Our own perception of whether we are suffering or not is quite important, because good qualities — loving kindness, compassion, empathy — will need to arise from how deeply our understanding of suffering is.

[00:12:54] Emma Slade: Whether from knowing it in our own life or observing it in others, and often we will have quite a narrow definition of suffering actually. So some forms of suffering are very obvious and they’re mostly to do with the physical form, right? But when we look at suffering from a Buddhist point of view, it’s much more likely to be a mental state of suffering. Once we are open to a broader definition of suffering, then our relationship with compassion to ourselves and others will definitely deepen and become more profound.

[00:13:27] Emma Slade: The Buddha sometimes he’s called the first psychologist, isn’t he? Because he really looked at suffering as a mental state, arising from our response to things or rising from our understanding of reality.

[00:13:40] Emma Slade: That means that with greater understanding, and study and the courage to really look at that process of what goes on in our mental responses that leads to suffering. That means we can also change it. It’s very important to be able to recognize one’s own state of suffering. It’s not failure, the Buddha said that, we really have to understand the truth of suffering.

[00:14:02] Cheryl: I would love to go back to walking the wild Bhutan trail. How are you preparing?

[00:14:07] Emma Slade: Oh my goodness. Don’t even ask me that. I’m doing a lot of retreat and so mentally I feel I’m very strong. But physically, I’m nearly 59, right? I may be mad. I just have a strong belief that I can do it and I I must do it for the children.

[00:14:23] Cheryl: And, and is there one key message that you would like people who are following your trail to take away?

[00:14:31] Emma Slade: If you are going to help others, you have to stretch yourself outside your comfort zone.

[00:14:36] Cheryl: That’s beautiful. And how, how can we follow with you?

[00:14:40] Emma Slade: You’ll be able to follow me on Facebook and Instagram under Emma Slade. You can look at the charity website openingyourhearttobhutan.com that has the campaign for the walk and, if people can donate the price of a meal or an outfit or a holiday, they can donate. If they want to come and join me, and do some fundraising for it, then they should get in touch.

[00:15:00] Cheryl: And what would success look like for you?

[00:15:02] Emma Slade: Getting to East Bhutan will be the first thing. Getting there alive, not being eaten by a bear and kinda like not falling down anywhere. I’d like to raise a minimum a 100,000 pounds because it will secure the future of the school for over two years. Fundraising is never easy. And right now I know things are quite turbulent in the world, and usually when things are turbulent and uncertain, people become fearful.

[00:15:32] Emma Slade: And when people are fearful, we know from neuroscience, let alone Buddhist studies, that they retract, right? They shrink into themselves. So it takes particular Bodhisattva motivation to keep that wide compassion at times like this, I think.

Buddhist Youth Network, Lim Soon Kiat, Alvin Chan, Tan Key Seng, Soh Hwee Hoon, Geraldine Tay, Venerable You Guang, Wilson Ng, Diga, Joyce, Tan Jia Yee, Joanne, Suñña, Shuo Mei, Arif, Bernice, Wee Teck, Andrew Yam, Kan Rong Hui, Wei Li Quek, Shirley Shen, Ezra, Joanne Chan, Hsien Li Siaw, Gillian Ang, Wang Shiow Mei, Ong Chye Chye, Melvin, Yoke Kuen, Nai Kai Lee, Amelia Toh, Hannah Law, Shin Hui Chong, Dennis Lee