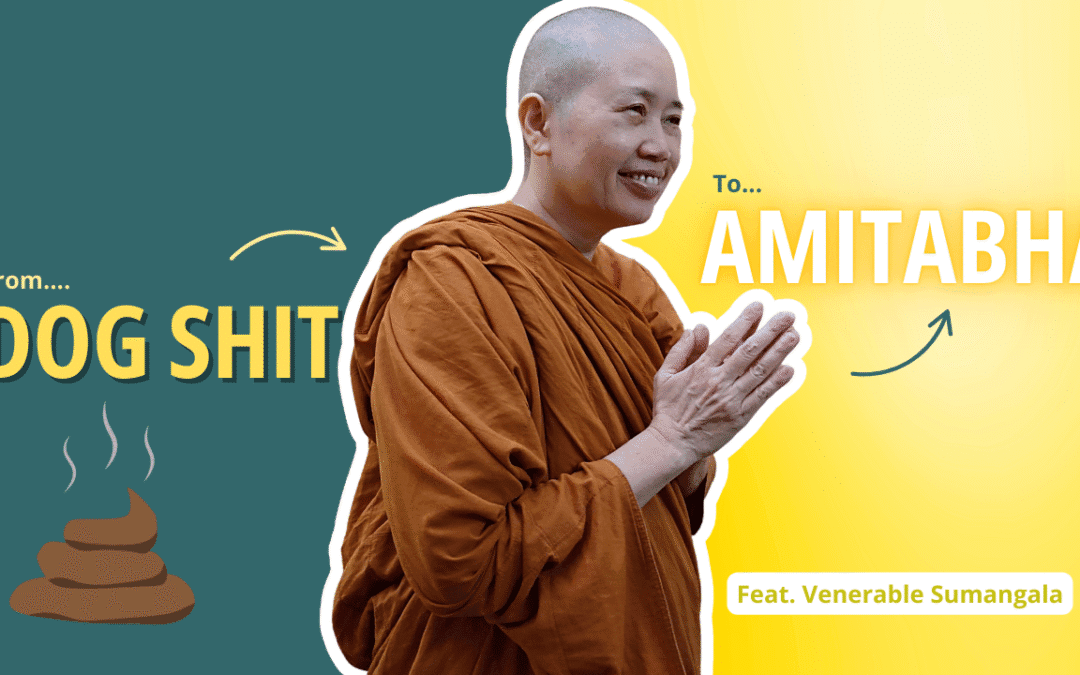

In this episode of Handful of Leaves, Venerable Sumangala shares insights on the practice of letting go and renunciation, emphasising the importance of inner transformation and understanding suffering. She explains how letting go of attachment to ego and external perceptions leads to true freedom and happiness, while still pursuing goals with a balanced approach.

Venerable Sumaṅgalā Therī is the Abbess of Ariya Vihara Buddhist Society and is an advisor of Gotami Vihara Society in Malaysia. She is one of the recipients of the 23rd Anniversary Outstanding Women Awards (OWBA) 2024, in honour of the United Nations International Women’s Day.

She holds a B.A. in Psychology and in 1999, she completed her M.A. in Industrial and Organizational Psychology, both from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Furthering her academic and spiritual education, Ven. Sumaṅgalā Therī obtained an M.A. in Philosophy (Buddhism) from the International Buddhist College, Thailand in 2011.

Her formal journey into monastic life began in 2005 when she left the household life to become an Anagarika at the age of 19. Her ordination as a Dasasil (akin to a Sāmaṇerī) took place in November 2008 under the sacred Sri Mahābodhi at Bodhgaya, India. On 21 June 2015, she took her higher ordination under the guidance of preceptor Ven. B. Sri Saranankara Nāyaka Mahāthera – the Chief Judiciary Monk of Malaysia, and bhikkhuni preceptor-teacher Ayya Santinī Mahātherī of Indonesia.

In 2015, she pioneered the formation and registration of Ariya Vihara, Malaysia’s first Theravāda Bhikkhunī Nunnery and Dhamma Training Centre. In 2019, she received a government allocated land for the building of the project with construction to commence in the first half of 2025.

True liberation comes from letting go of the ego and not creating more attachments to identity, fame, or success.

The Four Noble Truths guide us to understand that suffering is a result of attachment, and by letting go of desire, we can end suffering.

Achieving goals and success is natural, but it is important to not become attached to the outcome. Focus on the process and the wellbeing of others.

Full Transcript

[00:00:00] Venerable Sumangala: If we live by how other people perceive us, we never live our life.

[00:00:06] Cheryl: Welcome to the Handful of Leaves podcast.

[00:00:08] Cheryl: My name is Cheryl, and today I have a surprise guest host joining me, Soon.

[00:00:14] Soon: Hi everyone. it’s good to be here.

[00:00:18] Cheryl: So today we have a very interesting topic, which is called letting go of becoming. And sometimes the practice is described as going against the flow. And living in the material society seems to be opposite from the peace and zen of the spiritual practice. It’s a lot of becoming to do, milestones to achieve.

[00:00:39] Cheryl: So join me with my co-host, Soon, as we find out about we can balance letting go with the gettings, achieving and becomings of the world. We will speak to Venerable Sumangala, who is a fully ordained nun of 10 vassas to learn more. She is also the president of Ariya Vihara Buddhist Society, Malaysia’s first Theravada (add b-rolls) Bhikkuni Nunnery and Dhamma Training Center, and she is also an advisor to Gotami Vihara Society in Malaysia.

[00:01:09] Cheryl: Welcome, Venerable Sumangala.

[00:01:11] Venerable Sumangala: Thank you.

[00:01:12] Cheryl: You’ve mentioned in previous interviews about your journey on why you became a nun, and one quote that really struck my heart was that you said, when one has a glimpse into the noble truths, it is natural for one to be a renunciant in the Sangha rather than wanting to become a nun.

[00:01:32] Cheryl: Can you please share more on this?

[00:01:34] Venerable Sumangala: Actually from the question itself, we can see there are a few keywords. First is renunciation and then the wanting. Renunciation, in Buddhism is not just about giving up material things, but it’s actually an internal transformation. It’s an internal transformation rooted in insight, means something you have seen directly into the nature of reality. This nature of reality in common word, we say suffering. But I think if we look deeply is the constant change of everything. And also there’s an end to that. To an end to suffering. So when one actually deeply understands the 4 Noble Truths, seeing there is suffering in our life, not life is suffering, yeah? So two different things. There is suffering. So this suffering doesn’t exist by itself. There is a cause to suffering. So if you know the cause, then if you can eliminate the cause, then of course there’s no suffering. So therefore there’s an end to suffering. There’s a way, a gradual training that we can practice that can end our suffering. Because most of us, what we look forward is to be happy, to be free.

[00:02:46] Venerable Sumangala: So we must know how to get there. And the Buddha has provided us this path. Renunciation means we let go attachment and desire more easily when we understand this. True renunciation stems from wisdom and insight in the nature of suffering and working towards ending that suffering. But where else when we want to become, then it is suffering itself because we are actually attached to the idea of identity, fame, and name.

[00:03:20] Venerable Sumangala: And so therefore, it is so important that when we seek for something, the practice is very important. The inner transformation is very important so that we truly see the reality. And then from there, I think renunciation will take its own place. So true liberation actually comes from letting go of the ego, not creating more ego. We may aspire, but then the working on it, the practice is very important.

[00:03:48] Soon: Thank you Venerable Sumangala for that sharing. We are just curious, what’s the most difficult thing that you have let go of and was there any insights and wisdom that helped you, “Okay, it’s time to let go.”

[00:04:00] Venerable Sumangala: At that time actually for me is just to make my mother feel comfortable, but the spirit in my heart is actually burning to be very firm that, you know, that will be my path. One of the learnings that I have about this letting go and from lay life and how people view about life and renunciation too. So, for example, last time when I was still a layperson, I went for a pilgrimage tour to India. And we have this opportunity to shave, and that time I think it was still quite new. That was around 2003.

[00:04:34] Venerable Sumangala: Before that I have the idea of shaving and I used to take my long hair and look at a mirror to see how I looked like. But then when the opportunity came, I kind of hesitated. Because at that time I’m a branch manager and it’s very near to New Year. I’ll be meeting a lot of people, a lot of social function, and then how could I probably answer people, right? So the first thought is that, should I, should I not? Second time again, I was still pondering, but then suddenly my friend told me, she said, “I think you will shave”. I started to reflect. It’s because I’m looking at how people look at me after I shave, so that deterred me. But then interestingly, after the shaving, when I came back to Malaysia, I learned a lot about perception, about ego.

[00:05:26] Venerable Sumangala: First thing when my neighbor met me, she looked very taken aback, something must have happened to me, so I greet them as usual. Good morning, she answer back. And then when I go to the office, I dressed as usual with a bald head. And my executive was very shocked. And then business partners, suppliers, they get very shocked too, because in their thinking, is that what happened to Ms Ong at that time?

[00:05:54] Venerable Sumangala: And for business people, we love sensual pleasures, entertainments. So by looking at that, they will think that people who shave, maybe something shocking happened to their life or traumatic, whether they have gone out of their mind a little bit, or they heartbroken or they have something that’s wrong.

[00:06:14] Venerable Sumangala: When my bosses, we have dinner and then they bring their wife. The first thing they ask me, they say, “miss Ong, since when you are so bold, you know, fashion”. Because they’re into fashion, so their perception is about fashion. So it is very cool, you know with the bald head.

[00:06:31] Venerable Sumangala: And then my boss, “why you shave your hair?” Because for him he has only little hair on his head. So everyday he has a comb and combs to cover his head, and there you are with very nice hair and then you just shave and then get bald. So he wished me, I wish you know your hair grow fast.

[00:06:49] Venerable Sumangala: Actually many different responses. And when I met one uncle in a supermarket, and he approached me, he said, “oh, sister, is your hair related to Buddhism?” I said yes. Then I told him that I went for a pilgrimage and then I didn’t know him and he didn’t know me, and he asked me, “would you like to come to my house?

[00:07:11] Venerable Sumangala: I have a Guanyin of about 500 years old. Would you like to come and have a look?” and there are other people, they shave and when they go back, the mother actually give them a house arrest, thinking that they will go forth, so they just lock them up.

[00:07:26] Venerable Sumangala: Everywhere they go, they follow. And I reflect back. It’s just a haircut, but can you see how people respond? If they think of sickness, they will think that they’re sick. If they’re into fashion, they think you are so cool. And then if they don’t have that, like, my boss the hair is so little and then they see, aiyo, why you give up your hair? So you can see actually how we perceive, how we live by other people’s perceptions.

[00:07:50] Venerable Sumangala: And I think the understanding that I have is that if we live by how other people perceive us, we never live our life. In understanding the truth, I think this is a very important thing because we always have that ego and that ego seeks to be validated by others. So how are we going to find peace and happiness?

[00:08:10] Venerable Sumangala: So letting go oneself, I think is the best of letting go because you no need to hold on to the idea of our self, an identity or image to be taken care all the time because of how other people perceive you, not how you are actually,

[00:08:29] Cheryl: I’m just thinking how we can integrate that into the daily life.

[00:08:35] Cheryl: Most people spend most of the time building their careers, so that identity also become very entrenched in what they achieve, the successes and failures that they bring. How can one practice letting go?

[00:08:46] Venerable Sumangala: Letting go, it’s not about abandoning everything. Letting go is internal insight that sees the true reality of what is. Let go of gripping on something or idea or attachment to an outcome.

[00:09:02] Venerable Sumangala: We keep thinking about the outcome or the success. When we have this idea, it makes us feel very tight and tense and stressed. Everything we do needs desire. Can you see when a person is sick, they don’t have any desire, then nothing happens, right? That in our normal life, even desire is a path under the four roads of success, or ways of success. The first one is chanda, means you must have the aspiration. So in this way, we have a duty to be done because we are still a human. We need to work for our bowl of rice. And therefore we must have the drive.

[00:09:41] Venerable Sumangala: Yeah. We must have the drive to do something which is in accordance to right livelihood. Letting go doesn’t mean we don’t do anything or we give up everything and then become a person who’s like redundant. No, we still have desire, we still do good things. We still also have our goal to be achieved. Let’s say if you are worker, we are paid to do our duty well. So the Buddha also advised us, we perform our duty to the best of our ability, skills. Therefore from there, I think it will lead to good result. And from the good result, it’ll be commensurated with legitimate reward. So it is a natural process.

[00:10:23] Venerable Sumangala: There is an order. For even work, for achieving wellbeing, our wealth. So all those need our desire to work well. But that desire doesn’t lead us to attachment. For example, in the company, and we start to have this idea, “I want to be promoted”. Yeah, the word “I want to”– “I”, the identity is there, “you want”.

[00:10:46] Venerable Sumangala: And so when we do that, then it’ll cause us a lot of stress. When I was working, after five years they interviewed me, “what do you think you will become three years from now?” You know what I write there? I said, “to be happy and to make others happy.” That’s all that, right? Right. That was what I think important in life.

[00:11:08] Venerable Sumangala: But when I work after five years, they have promoted me to become a branch manager. I contributed my part, my knowledge, my skill. I do it well. I do my best. It doesn’t mean that my desire for success is not there, but it’s just that I’m not attached to it, and the process is more important. We already set the goal, then we work on the way to achieve that goal.

[00:11:34] Venerable Sumangala: Then we just let that be the goal, because as we work on it, the goal is coming, the results are coming. We don’t keep thinking about the goal, (but) not doing the part or the necessary actions to achieve the goal. And secondly, in the process of achieving the goal, always remember that we work in harmony. Sometimes we want to achieve the goal, we forget about the process. So the people that work with us, we don’t care. We just want to achieve the goal. So we push them, we stress them out. Then achieve the result is not as what we think. We must always think our wellbeing and the wellbeing of others, and together we can achieve it.

[00:12:13] Cheryl: Letting go is not laziness. And I think you also really embody that, even as a monastic right now where you have so many projects, that you’re running, being the Bhikkuni Training Center and the Gotami Vihara Society. Would you be able to share an example how you are able to go of the outcome while still having that desire to progress the development of female monastics?

[00:12:41] Venerable Sumangala: Actually when I embarked on this path, I felt that monastic life would be the best in continuing this journey. At the same time, then I realized that I have the ability and capacity to also share and to help others who are keen on this path.

[00:12:58] Venerable Sumangala: So in the past, we will have to search on our own. Because we know that the Bhikkhuni revival took place in 1996, so it’s still very, very young, about 20 over years. And I think the best part of it is our lead chief. He’s one of the senior monks who has took his compassionate duty to make this happen in the world.

[00:13:22] Venerable Sumangala: So we are very fortunate in Malaysia in a way that we have a senior monk that who is well known, very respected, who took this path to establish the four fold assembly again. In the past, we only have three. Now we have four back as what the Buddha has set up. People sometimes ask me, “Venerable. Are you not stressed? There’s so many things that’s ongoing.” Sometimes I reflect that when we need to prepare, then we look at the capacity first. When I see that, when my capacity is able to cover additional things for the wellbeing of others, then I think it’s time to execute. Then I will do it.

[00:14:00] Venerable Sumangala: We start with like Ariya Rainbow Kidz program for family Dhamma education. Then we have more people and more capacity. Then I train some of them to also help out. And then after that, then I extend for retreats, then longer retreats and then camps, and then to now Ariya monastic and laity training program.

[00:14:21] Venerable Sumangala: We also look into that because the whole Malaysia, we don’t have any center specifically for the Bhikkhuni. So without a Bhikkhuni center, without a sīmā, then we would not be able to have this capacity to provide the proper way of renunciation and also for the training. Yeah. So it is so important.

[00:14:43] Venerable Sumangala: So the lead chief actually told me that in order for the Bhikkhuni order to flourish, we must have a training center for them, and we must organize a proper training program for the Bhikkhunis. You need to have somebody to lead, and then you mobilize other people to come together. Those like-minded people who also seek for this kind of practice.

[00:15:02] Venerable Sumangala: We are also very fortunate in a way that some of the Bhikkhu Sangha, they all come to also guide us, support us rejoicing with our good development and practice. Yeah, so don’t attach to it, do your best, and when a thing comes, we just pick it up. And then after it’s finished, then we go to the next. Rejoicing with every good things that we do, bring us a lot of energy and happiness.

Buddhist Youth Network, Lim Soon Kiat, Alvin Chan, Tan Key Seng, Soh Hwee Hoon, Geraldine Tay, Venerable You Guang, Wilson Ng, Diga, Joyce, Tan Jia Yee, Joanne, Suñña, Shuo Mei, Arif, Bernice, Wee Teck, Andrew Yam, Kan Rong Hui, Wei Li Quek, Shirley Shen, Ezra, Joanne Chan, Hsien Li Siaw, Gillian Ang, Wang Shiow Mei, Ong Chye Chye, Melvin, Yoke Kuen, Nai Kai Lee, Amelia Toh, Hannah Law