TLDR: We explore how Netflix shows, example the film “Hunger,” can offer opportunities for mindful contemplation of the Dhamma. We explore the dimensions of physical survival, sensual desires, and moral values.

Chilling Meaningfully with Netflix

Yes, we all know the euphemistic nature of the phrase “Netflix and Chill”. It is often characterized as a complete mental switch-off activity that is laced with sexual connotations.

Instead of engaging in either people watching or meditation, Netflix might be the band-aid solution for some (like me I admit) to ‘occupy’ time on seemingly long train journeys and bus rides.

Can we avoid wiling away precious time even as our eyes remain glued to the screen? How can we chill meaningfully with our favourite Netflix show?

As an avid Netflix enthusiast who often harks back (knowingly) to the screen on buses and trains, I will be sharing how the newly launched Netflix film Hunger (2023) has created room for me to mindfully tease out Dhamma and chill in a meaningful manner.

Spoiler alerts ahead!

HUNGER (2023): A Brief Sypnosis

Set in the bustling global city of Bangkok, Hunger (2023) narrates the story of young Aoy, a talented cook who aspires to enter the world of fine dining to become a professional chef.

Despite being reprimanded severely by master chef Paul for her incompetence in the kitchen, Aoy bites the bullet, practices hard and eventually gains the recognition and status she craves for.

Although she is now at the apex of her career, she does not feel a sense of complete satisfaction. What was she really striving so hard for? What are the trade-offs she has to make from this insatiable appetite?

After realising some important truths, she decides to throw the apron (pun intended) and truly be her own chef back at her modest family restaurant.

Here are three levels of hunger that the film explores!

LEVEL 1: Neutral Hunger for Physical Survival

The first dimension of hunger which the film portrays deals with physical hunger. As depicted in the film, many homeless and malnourished were lying along pedestrian walkways, curling into a ball as they quietly withstand their hunger pangs.

Without food, physical suffering (dukkha) in the stomach will likely hinder peace of the mind.

Although these scenes in Hunger (2023) may seem very trivial, hunger is a very real problem faced by many on a day-to-day basis. Living in a developed country, we may simply gloss over physical hunger and take for granted the food we consume every meal.

This first level of hunger ties in beautifully with the Sukha Vagga which mentions how hunger (as in the physical kind) is the worst kind of disease which needs to be addressed before realising Nibbana.

Subjected to extreme states of physical hunger, the mind cannot settle down quietly to focus on the spiritual path, constantly disturbed by bodily demands.

203. Hunger is the worst disease, conditioned things the worst suffering. Knowing this as it really is, the wise realise Nibbana, the highest bliss.

LEVEL 2: Negative Hunger for Sensual Pleasures

The second dimension of hunger which the film portrays deals with our sensual desires. For the wealthy elites, food goes beyond pure sustenance.

Instead, food becomes a status symbol and an unforgettable experience. As the film suggests, theme parties are often thrown by high-rollers to give their guests a once-in-a-lifetime sensation.

From ‘Blood and Flesh’ (see picture above) to ‘Gladiator’-like settings, food becomes an interesting medium to tantalise one’s senses.

When this fleeting experience is over, what is ultimately left is the continuous craving for morE, moRE and MORE!

As peak experiences vanish, dissatisfaction arises. Conditioned to continue experiencing unique and out-of-the-world experiences, wealthy elites splurge on chefs like Aoy and Paul to materialise these experiences. However, when these extravagant food ‘performances’ are over, pleasant feelings fade and cease, perpetuating the vicious cycle of dissatisfaction once again.

As mentioned in Nandaka’s Exhortation, feelings (vedanā) are meandering patterns which arise, persist and fade perpetually based on a corresponding condition. Clinging on to pleasant feelings brought about through food will only lead to greater unhappiness and dissatisfaction.

146. Pleasant feeling is impermanent, conditioned, dependently arisen, having the nature of wasting, vanishing, fading and ceasing.

Majjhima Nikaya: Nandaka’s Exhortation

LEVEL 3: Positive Hunger for the Superego

The third and final dimension of hunger which the film portrays deals with this nebulous idea of a superego (see the journal article written by Nass, 2017).

The superego is concerned with social rules and morality – similar to what people call as their “conscience” or their “moral compass”.

For example, I might be certain nobody will notice if I steal something. However, knowing that stealing is inherently wrong, I decided not to take anything even though I probably wouldn’t get caught.

This ‘wholesome’ hunger to right the wrong, be utterly real, avoid guilt and remove shame makes us truly human. In the film, when master chef Paul was cooking an endangered hornbill for a wealthy diner, Aoy felt completely disgusted by this ruthless act which goes against her personal morals of not killing protected wildlife to simply appease the ‘3-inch tongue’.

This breach in her deeply-rooted values prompts Aoy to leave the patronage of her master and chart her own culinary path.

Similar to the notion of the superego, the Buddha’s Discourse to Visakha spells out the importance of wise shame (hiri) and wise fear (ottappa) as the guardian of our thoughts, speech and actions.

Without a specific catalogue of principles and rules to tell us what is considered right or wrong, we can only rely on our trustworthy companions (hiri and ottappa) to navigate this VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) world we live in.

One who has shame (hiri) of doing evil, and fear of doing evil (ottappa), the two qualities which are called “the world guardians”

Visakhuposatha Sutta: The Discourse to Visakha

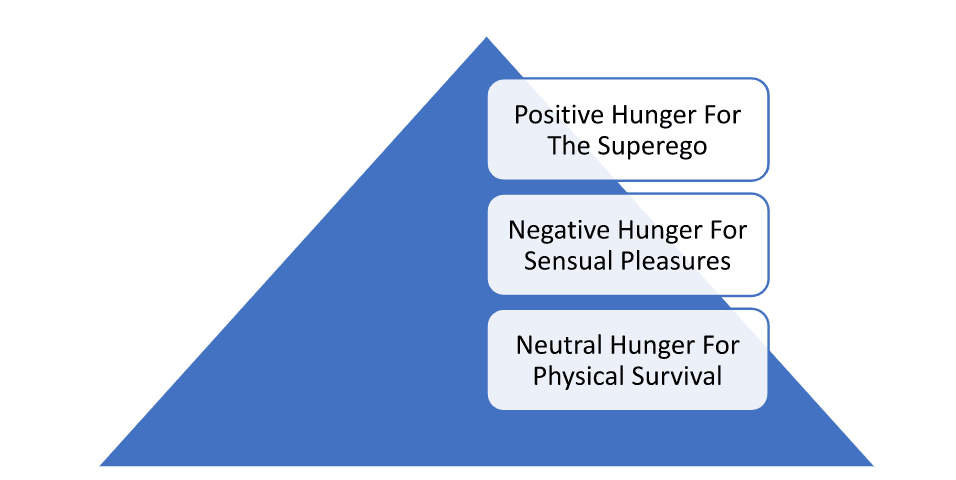

The Hunger Pyramid

In a nutshell, the dimensions of hunger in Hunger (2023) can be illustrated in the pyramid below:

From Binge to Mindful Watching

In conclusion, Hunger (2030) has provided me with a fine-grained analysis of different dimensions and understandings of hunger.

While neutral hunger for physical survival is a given to generate energy for mental cultivation, more attention should be paid to both negative and positive hunger.

Synonymous with greed (lobha), negative hunger is the craving for things that we don’t really need.

Positive hunger through discernment, on the other hand, drives us towards the highest good. Just like what Ananda, Buddha’s attendant, advised Brahman Unnabha in Kosambi, it is possible to abandon desire by means of desire.

The desire to do good, avoid evil, conform to hiri and abide by ottappa are merely Dhammic ‘tools’ and ‘vehicles’ to carry one towards ultimate bliss.

When the highest good (nibbana) is attained, these positive hungers (desires) must eventually be allayed and forsaken.

For lay watchers like myself, this aspirational energy derived through such positive desires and hunger is important. Without these ‘desirable’ instruments, it might be very challenging to navigate tactfully through the vicissitudes of this life.

Whatever desire he first had for the attainment of arahantship, on attaining arahantship that particular desire is allayed. … So what do you think, brahman? Is this an endless path, or one with an end?”

Brahmana Sutta: To Unnabha the Brahman

Instead of purely binge-watching Netflix on a mental shutdown mode, why not take the next train journey or bus trip as an opportunity to practice mindful-watching?

Tying back what we consume to the Dhamma can help us find deeper meaning in the mundane routines of life.

Wise Steps:

- Watch to destress but also watch to skilfully exercise the Dhamma. Netflix can indeed be a very powerful medium to make Dhamma come alive!

- Relate your personal experiences with the series you are watching. A mundane everyday experience of consuming food can actually be your ‘teacher’ for life!

- Hunger is ultimately a choice! Choosing the wrong kind of hunger invariably traps you in this vicious cycle of suffering. Choosing the right kind of hunger may be the key to emancipating yourself from this endless samsaric cycle.