TLDR: Raised in a devout Buddhist household, the writer reflects on their departure from religion as a disinterested teen, only to return in their twenties when the Buddha’s teaching about suffering finally began to resonate. After facing suffering and craving, this is their story of rediscovering meaning in the Dhamma they once turned their back on.

Growing up Buddhist

It was the 2000s: I had dial-up internet, Club Penguin, and Dharma class.

Every weekend, while the cool kids in class congregated at white-marbled chapels in town, I would head to a nondescript Buddhist centre in Geylang for my version of Sunday school. The door would creak open to rows of peers listening attentively. I would settle down, fold my legs crosswise, and diligently wait for break time.

The classes were a one-woman show. Teacher Lillian (not her real name) would read us legends about the Buddha’s past lives in a gentle lilting voice, speak of compassion, and prepare biscuits for the tea break.

She did this for nothing in return, collecting only $10 every four months to cover the cost of food for a whole semester.

Most of what she taught went through my ears and out the window. Nearly 20 years on, I admit that I don’t remember much, except for a frequent refrain that Teacher Lillian took pains to deliver: desire and ignorance, she often reminded us, lead to suffering.

Temple Dropout

Growing up privileged, there wasn’t much for me to suffer about beyond homework and piano lessons.

In a world entertained by Facebook and Harry Potter, I felt that the easiest way to “‘end’” the suffering of the hour was to feed that craving.

By my early teens, it seemed nonsensical to sit through alien-sounding prayers and elaborate pujas that lasted day and night.

To me, this mat torture was an eccentric way of life too far divorced from a teenager’s reality.

Even if there was a way out of suffering, I wasn’t convinced that the path consisted of endless chants and lengthy rituals that my 13-year-old self could scarcely understand.

As doubt set in, I eventually just could not be bothered with religion.

I spent my next 10 years as a ‘staunch agnostic’. When it was time to collect my national identity card in secondary school, I very resolutely told the administrative staff – who was collecting ancillary data – to remove “Buddhist” from my record.

At home, when I was from time to time invited to donate some of my ang pow money to help build a monastery near the Himalayas, I would roll my eyes in defiance.

What Lies Beneath Wanting

In the end, there is nothing quite like bout after bout of personal tragedy and calamity that pushes one to take a good hard look at reality.

I had my first taste of mortality in my early twenties.

With my life ahead of me, I sat in the doctor’s office while she delivered the sobering news: having thankfully escaped a diagnosis of the big C, I would nonetheless have to return every six months for the rest of my life.

Thus began a downward spiral – the realisation that I could not escape bodily pain, illness and death, yet helpless about what to do in the face of that suffering.

Still looking for a way to numb my pain, I distracted myself with the sweet oblivion of Netflix, dating, and chasing conventional success.

I hit my lowest of lows in university. In the thick of a recession, internships were scarce and on top of that, I felt the crushing pressure to maintain a perfect GPA.

I had unwittingly sequestered myself into a circle of ambitious peers who were sprinting ahead at full speed towards lucrative careers – relationships, friendships, health, and even morality be damned.

Do Something, or Forever Be a Failure

In an environment like that, the upshot was clear: make something out of yourself now or die a failure.

After a decade of straight As and dogged overachieving, I did not know what else to do. Status, competence, and prestige had already formed the basis of my self-worth.

One day, while doomscrolling on LinkedIn in the wee hours of the morning, I caught myself wishing ill upon a successful someone.

That jealous state of mind, full of greed and hatred, shocked me to my core. Was this who I had become? This body will fade, death will come, and my blind ambition has brought me nothing but misery. I had nothing if not morality. And now even that, I had lost sight of.

Like a snippet of a horror movie, I could not unsee. From then, I could not kick this niggling suspicion that there was something fundamentally grotesque about our default state of being.

Teacher Lillian’s frequent reminder of the Buddha’s words had stuck with me, its veracity standing the test of time: desire and ignorance, indeed, do lead to suffering.

Having left Buddhism for a good number of years by then, I had long lost touch with religious vocabulary. Much, much later, when my foray into the dhamma prompted me to explore the Pali Canon, I would find this nugget of wisdom nestled within the Buddha’s first sermon:

The Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (SN 56.11) outlines the Four Noble Truths: the truth of suffering, the truth of its origins in craving, the truth of the possibility of its cessation, and the truth of the path leading to its cessation. This path, known as the Noble Eightfold Path, provides a practical guide to cultivate awareness, develop wisdom, and gradually free ourselves from the cycle of suffering. It encompasses Right View, Intention, Speech, Action, Livelihood, Effort, Mindfulness, and Stillness.

Turning Away With Relief

Granted, this ‘default state of being’ can feel nigh impossible to resist.

In the Māgandiya Sutta (MN 75), the Buddha uses a powerful analogy to illustrate the abandonment of passion for sensual pleasures. He describes a leper with open sores who finds temporary relief by cauterising his wounds over a pit of burning embers. Although painful, this process provides a fleeting sense of pleasure for the leper. When cured, however, the former leper would recoil from the burning pit, understanding the true nature of that false “pleasure”.

Similarly, the Buddha explains, those still caught in the grip of sensual desires continue to indulge in them, finding temporary satisfaction. However, when one abandons passion for sensual pleasures through seeing things as they are, they no longer seek gratification in them.

This is because they have experienced a superior form of happiness – “a delight apart from sensual pleasures, apart from unwholesome states, which surpasses even divine bliss”.

This process of becoming disenchanted with sensual pleasures often starts with the Buddhist concept of “nibbida”. It comes from the root words “ni” (“without”) and “vindati” (“to find”) – which when put together, quite literally means “not finding”. And thus not finding delight, one naturally turns away. Nibbida, while often translated as disenchantment, disillusionment or even revulsion, is not a negative or depressing state. Rather, it can be experienced as a profound sense of relief and liberation.

In Good Company

By the time I graduated from university, I was thoroughly sick of living in constant misery. Having glimpsed at the causes belying my perpetual unhappiness, I started to cautiously dip my toes back into Buddhist thought. But I remained reticent about organised religion, choosing instead to accept the loneliness of my eccentric worldview. One day, a week after yet another Covid Christmas, feeling despondent about the quick depletion of my twenties, I finally gave in and signed up for meditation classes at a Buddhist centre in Geylang

As luck would have it, I went for the first session, nodded off during a 2-minute sit, and never went back.

I continued to spend many late nights googling random things that toed the line between dhamma and entertainment. My new hobby was to click aimlessly on Wikipedia, reading anything from Thich Nhat Hanh’s biography to Nagarjuna’s mind-boggling logic of the Catuskoti (a particular system of argumentation). Sometimes, I would end up on Reddit, where fellow sceptics shared hilariously crass memes that married religion with profanity. When humour ran out, I would then retreat to the comforts of Instagram, where trite as they were, quotes about inner peace overlaid on bodhi tree motifs brought me a limited kind of relief.

With all that random clicking I was doing, it is no wonder that I eventually clicked my way into Handful of Leaves. Upon reading the articles on HOL and browsing the author profiles, my first response was sheer amazement that young Buddhists existed in Singapore.

After all, I had spent an entire childhood being one of the only young attendees at Buddhist spaces. Still incredulous about their existence, I binged-read article after article, eventually chancing upon the Dhamma Assembly for Young Working Adults (DAYWA), a community of young Buddhist practitioners in Singapore.

My first encounter with DAYWA members took place on the last Wednesday of the month at a coffee shop in Telok Blangah. Some folks were clad in office wear and others in gym attire – as I looked around me, I once again could not help feeling amazed that young Buddhists existed. I shovelled down a tasteless mee pok, exchanged droll quips with a new acquaintance, and later tagged along to meditate in a quiet space. My first session serendipitously provided the perfect blend of peace and mirth. I knew quite instinctively that I had stumbled my way into something precious.

I had on my own, already started to dust off the sand that had been obscuring my worldview. But it was an unspeakable relief to finally meet kindred friends that would eventually make the eightfold path a lot less lonely.

Conclusion: This Path, That Path; Your Path, My Path …?

Now that I have returned to Buddhism, I have on occasion found myself drawn into sectarian conversations, perhaps an inevitable response when others learn of my background.

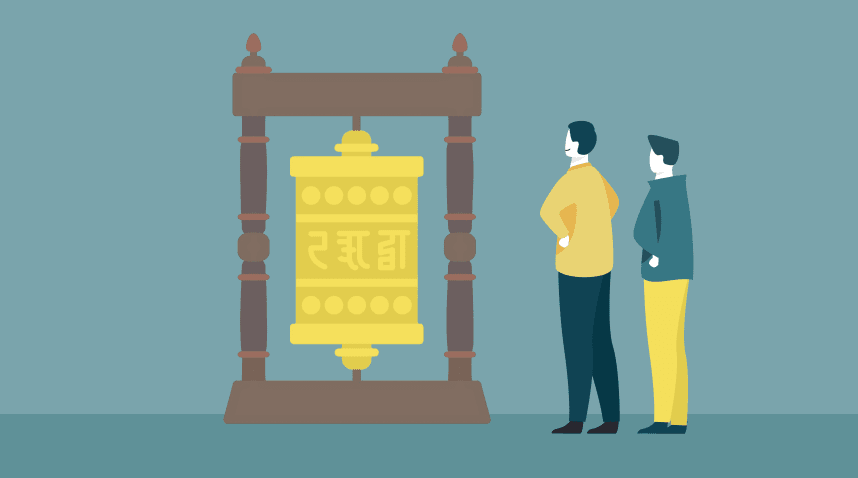

Out of part curiosity, part nostalgia, and part longing for my history to be understood by someone, I recently brought a friend to visit the Buddhist centre of my childhood. With the support of the laity, what was once a dilapidated corner shophouse sprawls six storeys today. On entry, I am greeted by a pair of gold-painted deer perched on a wide maroon awning. A while later, my friend joins me in gawking at the only furniture I recognised: a standing cylindrical prayer wheel that came up to my chest, replete with Sanskrit inscriptions. I thought I remembered it to be taller than me. As muscle memory sends my hands clockwise, I spot a stooped figure perusing the notice board.

“Teacher Lillian?” She peers over her reading glasses at me. To my surprise, a spark of recognition sets in. When she finally breaks into a smile, the lines on her face deepen to speak of the years that have gone by.

We begin to speak haltingly. Like any well-intentioned auntie at Chinese New Year, she asks if I am well and making a lot of money. I tell her I am well.

I enquire politely about the Sunday class. She titters ““Cannot find students already lah! How to get little kids interested? Need to find games to play lah, think how to teach and entertain them lah… I am just one person, so no more already lah.” Her tone is decidedly unsentimental, but I catch a hint of defeat.

Does Buddhism Have a Marketing Conundrum?

Her response brings me no surprise. Despite clear evidence of fiscal support, the renovated halls are filled with greying heads. I think of how deeply grateful I am to have found my kalyana mittas (spiritual friends). I think back to when I first lost interest in the religion and wonder if Buddhism has a marketing conundrum.

Our latest government census from 2020 reports that nearly a third of Singaporeans identify as Buddhist. When it comes to the salience of religion in Singaporean society, however, this figure might not paint the full picture. A separate study conducted by the Pew Research Centre in 2022 found that only 20% of Singaporean Buddhists view religion as ‘very important’ in their lives. The reported figures for other major religions in the country are more than two to four times higher.

Back at the temple, my mind drifts towards suffering, its origins, its cessation, and the path leading to its cessation. I think about how these truths can stare us Buddhists in the face yet remain elusive.

My thoughts turn to Teacher Lillian and the years she spent introducing the dharma to rowdy kids. I think of how I sometimes react to artefacts of my past with indifference at best, and at worst, with derision and resentment.

As I watch her retreat slowly towards the sound of bells and drums, that resentment starts to give way to a humble kind of gratitude. Gratitude to the ones who first introduced me to the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path.

Wise steps:

- If one is unhappy, reflect to find the cause of it – do not just stop at the first answer, continue to thoroughly reflect to find the root of this misery.

- Reflect on how you spend your time daily – how much of it is just a distraction from suffering?

- Reflect on what you are pursuing as a priority in life – does it bring you true, lasting happiness?