TLDR: The mind can feel chaotic with the presence of defilements. When doubt arises, try doubting the doubt to set the ground for clarity to arise. The teachers’ guidance can also help in the situation and as an object of recollection after returning to daily life.

I shared the first part of my experience of an 8-day retreat in Wat Marp Jan here, summarising my experiences in the environment. This part will summarise observations of my internal world, which may or may not be caused by external situations.

Doubtful mind

Doubt arose in the restless mind on the first few days. I found myself disliking the unfamiliar way the Dhamma talk was conducted: the Thai part by Ajahn Anan that I didn’t understand which meant I had to wait for the translated part, the seemingly unstructured topics chosen for the session, the distractions of seeing the other monks having their meals during morning Dhamma talks.

There was so much resistance in my mind that I wondered if it was the right decision to join the retreat. I decided to take Ajahn Achalo’s suggestion to doubt the doubtful thought: “Who is doubting?”.

I asked myself if the doubt was reasonable, as there must be some validity to the method if these many retreatants decided that it was worthwhile to spend 9 days away from their daily lives to be here.

Keeping this in mind, I continued with the daily schedules and, fortunately, supportive experiences started to materialise. I watched how the resident monks acted with grace and intention, listened to how the visiting Ajahns expressed their respect for Ajahn Anan, and felt how Ajahn Anan slowly drew my mind in.

My mind shifted into a lighter mode in the middle of the retreat period, and I was more receptive to the way things were conducted.

The teachers show up

We were also privileged to listen to Dhamma talks from other visiting Ajahns during the week. Ajahn Achalo dialled in via Zoom to caution us that hindrances may be amplified during the retreat period (it’s totally accurate for me!); Ajahn Ñāṇiko from Abhayagiri Monastery shared about patience-endurance (Khanti) and faith (Saddha) in our practice; Ajahn Pavaro from Tisarana Buddhist Monastery gave advice on getting ‘back’ into daily life.

For me, the peak experience was when Luang Por Boonchu graced us with his presence. Ajahn Anan treated him with such high esteem, sharing that Luang Por Boonchu was the left-hand man of Luang Por Chah (while Luang Por Liem was his right-hand man).

Visually he may look like an unassuming older monk, but he emanated such a ray of joy (or perhaps equanimity) with his light-hearted mood. He encouraged us to remain mindful and see conditions as ‘just like that’, to continue with our practice, and try something we have not done before – if we’ve never meditated overnight, we should try it out (some retreatants did that with a joyful attitude).

I experienced this ‘old monk’ as the epitome of joy and love. I was in tears by the end of the session, overcome by the overflowing joy and bliss in my heart. Feeling embarrassed, I apologised to my chore-mate for having to compose myself before our cleaning duty. She just smiled and said, “That’s okay. I cried yesterday too.”

Last but not least, Ajahn Anan stood at the centre of my overall experience. Ajahn showed up as someone a little stern in the beginning, adding to the dislike in my mind. When I finally saw Ajahn Anan’s warmth and generosity over the next few days, my mind also slowly opened up to his teachings.

I noticed Ajahn’s emphasis on continuous practice and mind cultivation (he often closed his Dhamma talk by telling us to ‘Samadhi’ – just one word and everyone gladly followed).

When daily life ‘returns’ to us

Having been to two retreats, I now understand why retreats could progress one’s practice and deepen one’s faith in their practice. The secluded environment helps to highlight areas that are ready for exploration and progress. However, the practice does not (and should not) end when we leave the monastery compound, so the effort does not go to waste.

We can find appropriate ways to continue with the habit/practice cultivated during the retreat.

Ajahn Pavaro suggested that we bring our minds to meaningful moments during the retreat so that we can recollect and lighten our minds when daily/mundane life clogs our minds.

Incorporate mindfulness in daily small actions, e.g. be aware of the body when sitting in a traffic jam. With this, we can continue using the spirit already developed during the retreat into a more mindful life.

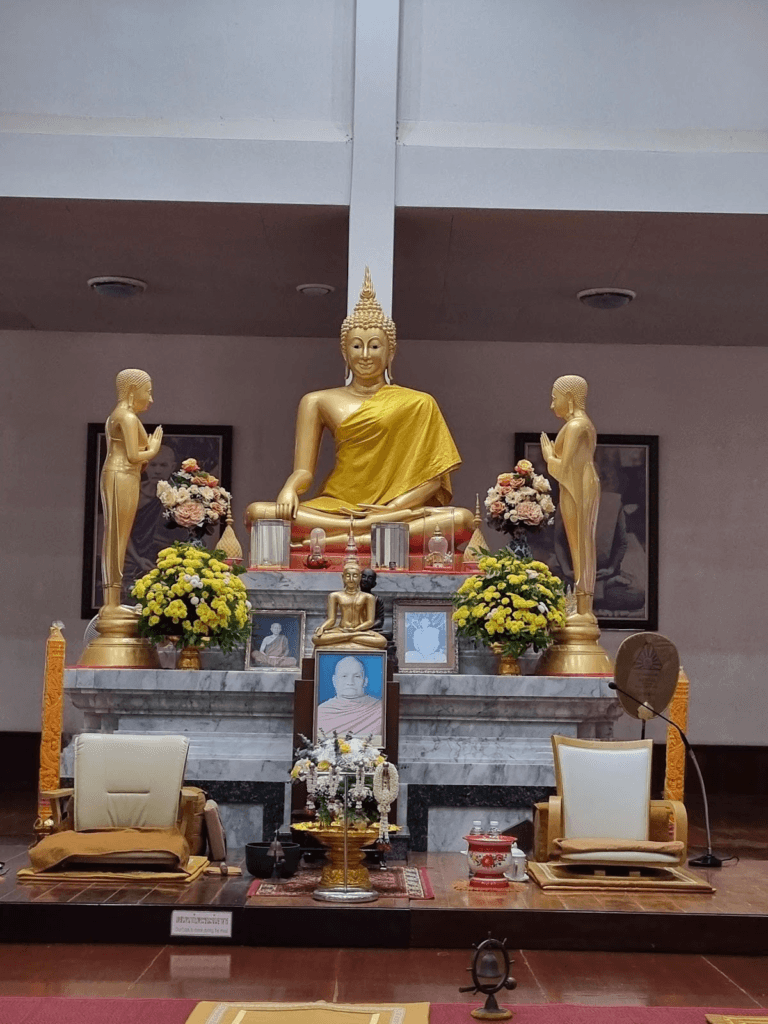

Buddha’s smile

I’d like to close off this sharing with a small realisation. When I first saw the Buddha statue in the Eating Hall, I recall thinking, “This Buddha’s face feels awkward”.

Towards the end of the retreat, I finally saw the compassionate gaze and smile. Of course, there was no change to the statue, only a change in my perspective and understanding. It’s human nature to form opinions based on our past habits, but there can be learning as long as we keep our minds and hearts open.

Cr: Author

Wise steps:

- The mind can play tricks, raising doubtful thoughts to discourage the practice. Try doubting the doubt to see the situation beyond our own liking/disliking.

- Remain patient when disliking arises. Once the ‘dust’ settles down, only can the mind see clearly.

- Retreat and daily life can feel like two opposite ways of life. We can apply small mindful actions to bridge the gap.