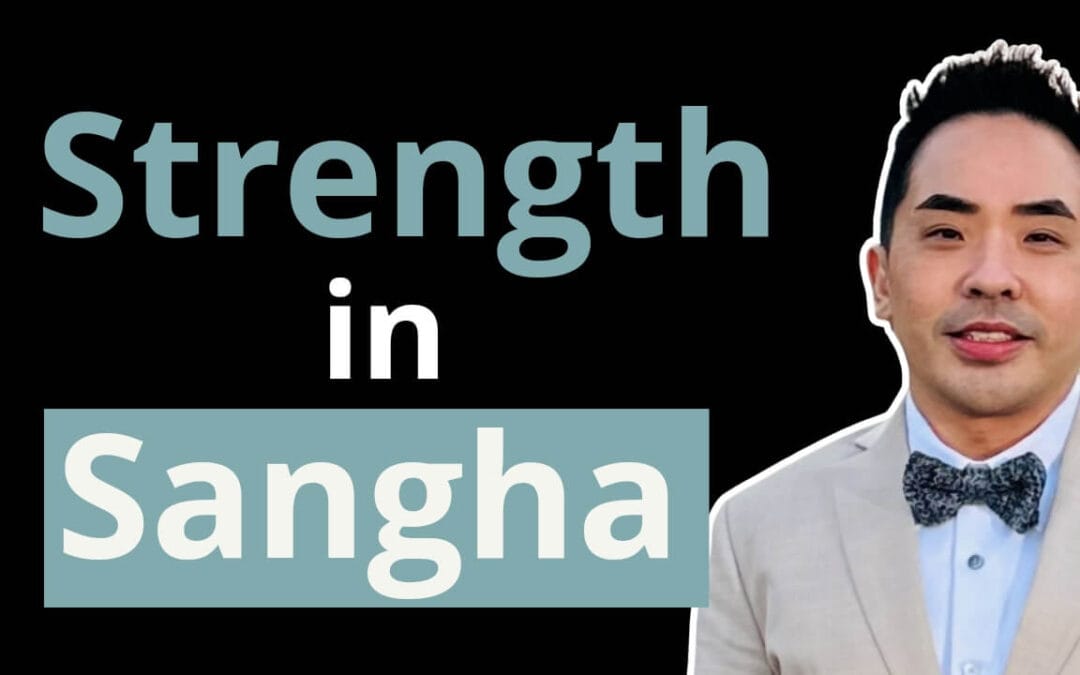

🤔 Ever wondered what it truly means to take refuge in the Sangha? 🌱 In this episode, Cheryl and Brother Chye Chye explore the importance of this practice for personal and communal spiritual growth by understanding:

☸️ The significance and qualities of the noble Sangha

🙏 How we can find balance in relating to the Sangha

🔍 Checks and balances within the Sangha ecosystem

Chye works in the wealth management industry. He not only plays the role of a banker to his clients but often as a counsellor, friend, confidant etc. As a trained engineer, he will often try to make Dhamma learning as simple and logical as possible.

Taking refuge in the Sangha, a core practice in Buddhism, goes beyond mere association—it signifies a deep commitment to learning and embodying the teachings of the Buddha. In a recent insightful discussion between Cheryl and Brother Chye Chye, the essence of going to the Sangha for refuge was explored, highlighting its transformative power in personal and communal spiritual growth.

Cheryl and Brother Chye emphasized that the Sangha consists of individuals who not only uphold but also live by the teachings of the Buddha. They embody qualities such as integrity and wisdom, serving as custodians of the Dhamma and an unsurpassable field of merit to the world. The Sangha inspires by teaching the Dhamma clearly and logically, motivated by compassion for the benefit of others, and without self-interest. They also inspire through their upright conduct, demonstrating integrity and adherence to Buddhist principles. These qualities collectively inspire practitioners by offering clear guidance and serving as authentic examples of living according to the Dhamma.

The discussion highlighted the importance of balancing the need for guidance from teachers with trusting one’s own mindfulness to progress on this path. This delicate balance ensures that practitioners benefit from the collective wisdom of the Sangha while also nurturing their self-reliance on this spiritual journey. When relating to monastics, it’s skillful to understand that bowing to them signifies respect for the entire Sangha community of the past, present and future. This practice ensures that our refuge lies in the qualities and collective practice of the Sangha, rather than solely in individual persons, thereby safeguarding our faith in the Triple Gem.

Delving into the nuances of community dynamics, Cheryl and Brother Chye Chye explored the significance of offering constructive feedback within the Sangha. They emphasized that fostering a supportive environment is crucial for growth and harmony on the spiritual path. By engaging in respectful dialogue and mutual support, practitioners contribute to a nurturing community that facilitates collective progress.

In conclusion, Cheryl and Brother Chye Chye’s discussion on taking refuge in the Sangha illuminates the profound implications of this practice within Buddhism. By embracing the qualities of integrity, wisdom, and communal support, practitioners not only deepen their spiritual practice but also contribute to the preservation and propagation of the Dhamma. Ultimately, the Sangha serves as a beacon of inspiration and guidance, guiding individuals on their journey towards awakening and enlightenment.

Full Transcript

[00:00:00] Cheryl: Welcome to the Handful of Leaves podcast. My name is Cheryl. And today I have with me a special guest, Brother Chye Chye.

[00:00:08] Chye: Hello, Brother Chye Chye.

Hello Cheryl. Hi.

[00:00:10] Cheryl: So Brother Chye Chye is a Dhamma practitioner, a student of the Buddha, and he loves cats and dogs. Yes, yes, yes.

I’ll let him introduce the names of his cute little cats and dogs.

[00:00:22] Chye: Okay I have a handful of animals at my place. So I have two dogs and two cats. My first dog is called Bodhi, and my second dog is called Metta. My two other cats, one cat is called Satta. The other cat is called Citta.

My aim is that you put them together then it means something like Bodhisatta, Bodhicitta.

[00:00:43] Cheryl: Last time I went to Brother Chye Chye’s house and it was quite funny because Metta was kind of hyper. And then I think Brother Chye Chye was scolding, Metta! Sit down! Metta! Stop it!

[00:00:56] Chye: No Metta already.

[00:00:57] Cheryl: Yeah, I found it so funny and ironic.

[00:01:02] Chye: Yeah, it’s very active, very active. Also means it has a lot of Metta for everyone. So it’s very friendly to everyone and wants to play with everyone.

Yeah, that’s right.

[00:01:09] Cheryl: Today I’ve invited Brother Chye Chye for a challenging topic.

So it’s relating to the idea of taking refuge in the Sangha, which we always do, and really wanting to dig deep to understand what does it mean to respect the Sangha, what does it mean to take refuge in them, and to what extent should we rely on them and on ourselves in this practice.

[00:01:39] Chye: Okay, okay. Let me answer the first part about taking refuge in Sangha. I think that’s what most Buddhists would do. And it’s commonly done, I mean, when you first become a Buddhist, you take refuge in the Triple Gem and one of them is the Sangha, right? So let me break it down into two parts, right? So one is taking refuge.

And one is the Sangha, right? So, what does taking refuge mean, right? So, by the word it means that you’re actually taking shelter? or you go to a place that’s very safe, right? Or someone or a place that you have trust and confidence in, right? Because when you are at that place or when you’re with somebody or when you’re with the object, it actually protects you from danger in whatever sense, right?

So typically when somebody take refuge in the triple gems, you also mean that you want to follow this path. You have confidence in this path to protect you from the danger of the world and all the dangers of the mind or the Akusala mind, right? The great, hatred, delusion. And it’s also coincidentally when you want to be a Buddhist, the first thing that you do is to take refuge in the Triple Gem, Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha, right?

So that is the taking refuge part. Then let me talk about the Sangha right? Ideally, Sangha in the Buddha’s time, it referred to the Ariya Sangha, right? That’s why in the recitation of the qualities of the Sangha, you talk about the four pairs of person, the eight types of individuals, right? And there’s nowhere that they talk about donning the robes. Right. It’s all about the qualities of the Sangha, right?

So Ariya Sangha means one who have realized at least a first stage of sainthood because in a Buddhist practice especially in the Theravada practice, when you practice Dhamma, you have different attainment, right?

So if you attain the first stage of Enlightenment, that qualifies you as an Ariya Sangha and in total there are four stages. Yeah. Okay. So that’s Ariya Sangha. But nowadays, conventionally, they are the monastic community who are in robes or they are ordained, right? And they are the representative of the monastic community, who devote their lives to the practice of Dhamma. And they’re important because they’re the ones who’ve shared, preserved and practiced the Dhamma for 2600 years.

And today we can still learn the Dhamma because of them.

So taking refuge in Sangha now has two levels. One I call the external level, right? So it’s about having confidence. in the qualities of the ideal Sangha, and also in the monastic Sangha community, which has helped to preserve the teaching until today. So that’s the external part, right? But more importantly, it’s also about the internal part.

Internal refuge to the Sangha, what does it mean? It’s about having that confidence in ourselves that one day we can be purified to become the ideal Sangha. So from external, it must come to internal. That’s why the Buddha said that, you know, in the Parinirvana Sutta, he said mendicants or bhikkhus, be an island unto yourself.

Now be your own refuge with no other refuge. What does it mean? If you look at the quality of the Triple Gem, the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha, we all can have the quality if we practice the Dhamma well and we follow the path. So that to me is taking refuge in the Sangha externally and internally. Yeah.

[00:04:58] Cheryl: And I’m very curious to hear from you about your journey in taking refuge in the Sangha.

How has that evolved from the first day you took refuge until today?

[00:05:09] Chye: Wow. Very different. It’s totally different. Because initially when I take refuge in the Sangha or in the Triple Gem, right? Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha, right? It’s really the form, right? The Buddha Rupa, the texts, the teachings, followed by the monastic form. But as you go deeper and deeper into the practice, you start to realize the Triple Gem, it’s about the qualities, the qualities of the Buddha. Although the Buddha is not around, but we can still feel the qualities of the Buddha, you know, the timeless teaching, the Dhamma and the Sangha who have practiced well and practiced right.

And because you take refuge in the qualities of the Triple Gem, you yourself will want to aspire to achieve those qualities in the Triple Gem. Something you’re confident in that you can achieve. Then you realize that actually the Triple Gem are all within us. We can achieve an awakened mind. We can taste the Dhamma. And Sangha just means that one day, we can be the ideal Sangha that the Buddha talked about. So right now, the Triple Gem has a very special meaning for me.

It means that I myself, if I walk the path correctly, the Triple Gem is inside me, and I take refuge in that Triple Gem.

[00:06:19] Cheryl: I find that so beautiful that you are able to take the journey from taking refuge of an external object to moving it into characteristics and qualities that you could embody within yourself.

[00:06:32] Chye: Yeah. So now taking refuge in the Triple Gem become very meaningful for me. It’s no longer something that’s external, but I’ve moved into the internal part of me that I want to achieve. I can achieve. I have the potential to achieve. Yeah.

[00:06:45] Cheryl: And can you share more about the qualities and I guess perhaps elaborating a bit more specifically on the qualities of the Sangha in the ideal sense that the Buddha expounded?

[00:07:00] Chye: Okay, if you look at the phrase, it’s talking about Sangha members who practice in a very honest way, practice correctly, and practice in a way that inspires people, right? And of course, if you practice that way, one day you can attain the fruits of the Dhamma or the fruits of the path.

And that’s why there are four pairs and eight types of individuals and that these are the people who we call the Ariya Sangha, right? These are the people that bring immense merits to the world. That’s why in the phrase it is said that they’re an unsurpassed field of merits for the world, because this group of Sangha, not only they are harmless, but they also are very beneficial to the world when they share the teaching, when they share the path, and when they guide you accordingly in the practice itself. And they’re also worthy of gifts, worthy of hostility, and worthy of offering, because they themselves have walked the path, they themselves have benefited from the path and have realized and now they share the Dhamma. And that’s the reason why they are worthy of all these offering, gifts and hospitality. So to me, this is the ideal quality of Sangha that is set by the standard and also something that we all can achieve. We all can achieve if we walk the path correctly.

[00:08:12] Cheryl: So you’re saying one was they walk correctly. Secondly is, they walk in an inspiring way.

[00:08:19] Chye: Yes. Inspiring way. That’s right.

[00:08:21] Cheryl: And I think two more would be with integrity and with insight.

[00:08:26] Chye: With integrity, honest, you practice honestly in a very honest way.

[00:08:29] Cheryl: Okay. And I think the point that you mentioned about inspiring is something very interesting because inspiring can be sometimes based on lay person’s expectations. So for example, I can feel a teacher to be inspiring because they sit in a very straight manner. But then sometimes I see another monastic member from a different tradition where they are constantly just scratching or fidgeting and they appear uninspiring.

But then I hear from other people that, Hey, this teacher is very well attained. So what exactly do you by inspiring? Is it through observing their conduct?

[00:09:07] Chye: I think there are two parts. One is observing what they say, right? How they teach and what they say, right? And Buddha is very specific about how one should teach the Dhamma.

For example, he said that the qualities of a good Dhamma speaker is one who can speak very clearly and one who can speak very logically. Clear and logical. And he also speak in a sense that it is out of compassion for people and for the benefit of people. And the fifth one is about not speaking because he wants to have anything for himself.

Right? So if you look at the qualities of a Dhamma speaker or someone who is inspiring, right? There’s nothing which talks about charisma. No, there’s nothing about charisma or how popular this person is. It’s about whether this person can guide you in a very clear way, logical way. And the thing that they speak is very beneficial to you as well.

So that’s one part about speaking the Dhamma. And second thing is about the conduct. That’s the reason why the Buddha also say that when you want to observe someone, you must observe for a time frame, whether his conduct is in sync with what he says. Let’s say this person says that I’ll keep the precepts, you must make sure that the conduct lives up to the standard of keeping the precepts of being mindful and things like that.

These are two things I observe in the Sangha. One is how they teach not in a charismatic way, but in a way that they are very clear in our teaching and beneficial to other people. And one is their conduct. Their conduct must be in a way that is inspiring in the sense that they are honest with the practice. They live up to the standard of whatever they say. So that to me is inspiring. Yeah.

[00:10:46] Cheryl: Thanks for very clearly explaining this. Yeah, because I think in the age of Facebook, I tend to find myself guilty of trusting a teacher a little bit more if they have more likes on their page, more shares, they’re more charismatic and popular and things like that.

Exactly. Yeah. Yeah. So, so thanks for, for bringing it back to the sutta and reminding us clearly. And at the same time, there are also a lot of news or articles about monastic members who kind of go sideways. So sometimes when I pay respect or meet a new monk that I’ve never met before, I can tend to be a little bit skeptical.

What is the way that we should relate to monastics skillfully? What are we paying respect to when we bow down to the robes?

[00:11:33] Chye: I think we have to be very clear that when we bow to a Sangha or to a group of Sangha, it’s bowing to the whole Sangha community of the four directions. In the past, present, and future.

And that’s what the Buddha said, right? If you bow to a Sangha, they represent the Sangha community. When you bow, it’s not bowing to the person itself, but bowing to the Sangha community, the community that preserves the Dhamma, that practices the Dhamma. And the Buddha specifically said in all direction, and in all past, present, and future.

And this is very important. Why? Because it’s again that we take refuge, right? We take refuge in the Sangha. It’s not about the person. We take refuge in the qualities. and in the community who practice well and practice together, right? And it’s important because if you take refuge in a person itself, what if the person doesn’t live up to the expectation?

Then either your faith will dwindle or your faith will just fall apart and then you lose faith in the triple gem. So that’s something that I always remind people to be very careful. When you bow to the Sangha, it’s really to the community, not to the person itself. Yeah. Cause sometimes a person can fall short.

We never know.

[00:12:46] Cheryl: That’s true. We’re setting ourselves up for disappointments if we just put our faith a hundred percent in a person.

[00:12:54] Chye: Correct. That’s right.

[00:12:55] Cheryl: I’m curious, in your journey as a student of the Buddha, how to find that balance on relying on your teacher’s guidance and relying on your own wisdom and mindfulness when you meet with challenges.

[00:13:09] Chye: I think you need both. You need both. A Dhamma practice requires two parts, right? One is the knowledge. Knowledge means the Dhamma, how to practice, what to practice, and what should you be experiencing with the practice.

So these are the Dhamma knowledge, right? The knowledge itself. The other part is the practice. It means that you put this knowledge into practice, right? And when you practice well and certain experience come through your practice, that’s according to the knowledge, that’s what I call insight.

So Dhamma practice means for the knowledge and the practical side starts to gel together and that’s the insight. Okay. So that’s, that’s for me the Dhamma practice. So to me, an ideal teacher or teacher should have this two parts come together, right? He should be able to give you the instruction and he should be the one that have realized some part of the instruction.

And that’s the reason why he goes to the teacher, to ask for guidance. When we practice or when we meet with any obstacle, we go to them, right? And to me, a teacher is important as well as our own practice. Why? It’s because sometimes the mind can play a lot of tricks on us. Sometimes we find excuses or sometimes we can be too overzealous.

And so that’s why we need a teacher to really guide us and bring us back to a balance. So to me, a teacher and your own practice, it must come hand in hand together. And it must be like that. Because even the Buddha said that, you must frequently visit a Sangha or visit a community to discuss Dhamma, to share Dhamma or to talk about Dhamma. And we also know that in the Mangala Sutta, one of the highest blessings is to be able to share Dhamma or to learn Dhamma from a Sangha community or a teacher itself. Yeah.

[00:14:54] Cheryl: Was there a time where you lean too much on one end or the other?

[00:14:57] Chye: Yes and no lah. I’m a Libra right, so Libra tends to be a bit more balanced. Me too, I’m a Libra! Are you a Libra too? Yeah, I’m a Libra. So, my logical and emotional sides can be quite balanced. So for example, let’s say I really like a teacher, I learn the teaching, and I feel that I’m too attached to the teacher, then I’ll pull back.

But if you want to know when you lean too much, it’s when you follow a teacher and you find that you just believe 100 percent the teacher without verifying. That’s, I think it’s a bit too much, right?

Or you do your own practice and believe yourself too much. That you don’t go to a teacher anymore, or you don’t seek guidance anymore, and become very egoistic, right? And so that’s also a danger to realize. So, a good balance is where there is a time for us to practice. And then when you meet your obstacles, there’s a time for you to discuss Dhamma with a teacher and to seek guidance.

So that to me is a well balanced practitioner.

[00:15:49] Cheryl: Wonderful. And I resonate a lot with that. I am the type who can become quite attached to a teacher. And then sometimes I notice that my mind becomes very biased when I see teachings from other teachers or other traditions. I’ll be like, but my teacher said it better.

[00:16:06] Chye: That’s right.

[00:16:06] Cheryl: Then that’s when I know, I need to check myself on this and watch this attachment.

[00:16:12] Chye: Right, right. I mean, all these are attachments, but sometimes it’s just like that. People will get attached to things that they like. So it’s also a practice for us to realize that it’s also attachment and pull back.

[00:16:22] Cheryl: And now we move gears a little bit. Sometimes you can hear criticisms about Sangha members, but sometimes it’s unfounded. You also don’t know whether it’s true or not. And we can get a bit confused. What is a practical advice on how we can go about being skillful?

[00:16:41] Chye: I think to me it’s about okay, if that particular conversation it’s not factual, it’s not helpful and not kind. I’ll typically just ignore it. For example, people talk about, oh, no, that Sangha member he look very proud. Not factual, right? Not factual and not helpful.

So I’ll just ignore it. I’ll just avoid discussing that conversation. But having said that, I also think that sometimes we have to give a benefit of doubt to people who are saying it. We must see where the person is coming from, right? If let’s say it’s a very genuine concern about a Sangha, then probably we can discuss about it with a very open mind and see where are the facts and what are the things that the person is trying to say. Because I find that sometimes in the Buddhist community, when somebody talks about Sangha, it’s taboo, it’s bad karma, right?

So we need to provide a safe place for people to express their genuine concern about a Sangha rather than brush it off. It’s a balance between assessing whether what they’re saying is helpful, is it factual or not? Or is it a genuine concern? If it’s a genuine concern, then probably we can explore and discuss about it so that this community can thrive.

This community can grow together and be honest with each other.

[00:17:53] Cheryl: Yes. And that is very helpful advice. Because I had a conversation with a friend recently and she was feeling very troubled by the things that she’s hearing. And the first thing she feels is that, Oh no, what is going to happen to my practice if my teacher is truly like that. And then the second thing is everyone say, don’t talk about this. Don’t talk about this. It’s bad karma. Exactly. Like you mentioned.

Negative things, we sometimes need to still bring it up in a skillful way. It’s for the longterm benefit for the community to thrive.

[00:18:25] Chye: Correct, correct. I think it’s important to create a safe space for people to really express their genuine concern.

But yet we also need to have a safe space for people who talk nonsense about Sangha, like very unhelpful, or even cast their own expectation on the Sangha, say he should like this, he should like this. So it’s a balance, right? And that balance comes with certain mindfulness. You check whether, Hey, he’s talking about this, is it helpful or is it real or is it factual?

So this is something that we had to take care of. Yeah, yeah.

[00:18:53] Cheryl: Then to what extent is it a layperson’s duty to provide feedback to monastic members?

[00:19:02] Chye: It’s. Absolutely a lay person responsibility really to me. If you go back to the Buddha’s time, most of the Vinaya came about because the lay people went and complained to the Buddha. And the Buddha said, yeah, it’s true. It shouldn’t be like that. So let me have the Vinaya rule about this. Yeah. So in the past it was like that. The lay people will go to the Buddha and feedback. So they’re like the quality control of the Sangha. And that’s how the Sangha community grow, and grow so much during the Buddha’s time.

Because there’s this mutual trust among each other that the bhikkhu teach the right Dhamma, and the lay people will also give feedback to the bhikkhus or the monastic Sangha. And to me, it’s important because we are the ones who support the Sangha. We are the ones who help the Sangha grow.

In a way, we are also responsible whether the Sangha are going the right or the wrong way. And to me, there’s a baseline. About the four Pārājika rules, right, because you know that monastic Sangha, there are different Vinaya rules, right? So if it’s about the four very serious rules that they shouldn’t breach, for me, I will just go to wherever the temple or to the place and give a feedback for them to investigate.

[00:20:09] Cheryl: It’s very clear cut on that.

[00:20:10] Chye: Yeah, that’s me. But for other things like minor issues, maybe the robes are improper, I don’t really bother. These are things that does not bring harm to other people. So my baseline is, if the conduct brings harm to other people, especially to devotees, for me, I’ll just voice out, because it’s really our responsibility to make sure that we check on each other.

So the Sangha teach us the Dhamma and we also help the Sangha to grow in a pure way.

[00:20:34] Cheryl: Thank you very much Brother Chye Chye for today’s short and snazzy episode where we learn how to relate to the Sangha skillfully, what it means to take refuge.

And I hope to all our listeners, you take away one or two points that help you to improve your practice and to continue to grow together with the Sangha community both in the external form as well as the internal qualities within yourself. Any last words?

[00:20:59] Chye: Yes. If you are interested in, I mean to me, if you want to grow in the Dhamma, have a relationship with Sangha, I think it’s good also to know what their rules are.

Right. A book that’s quite interesting, it’s called The Bhikkhu Rules for lay people. So it summarizes how should they conduct themselves and what are the rules and things like that. When you read all these rules, you’ll find that you’re very inspired by them because it’s such a thorough training for the monastic. So both ways, when you know it, you will roughly know how is it like, and you’ll also be inspired by the community.

[00:21:31] Cheryl: Thank you so much, Brother Chye Chye and to all listeners, see you again in the next episode.

Buddhist Youth Network, Lim Soon Kiat, Alvin Chan, Tan Key Seng, Soh Hwee Hoon, Geraldine Tay, Venerable You Guang, Wilson Ng, Diga, Joyce, Tan Jia Yee, Joanne, Suñña, Shuo Mei, Arif, Bernice, Wee Teck, Andrew Yam, Kan Rong Hui, Wei Li Quek, Shirley Shen, Ezra, Joanne Chan, Hsien Li Siaw, Gillian Ang, Wang Shiow Mei, Ong Chye Chye, Melvin, Yoke Kuen