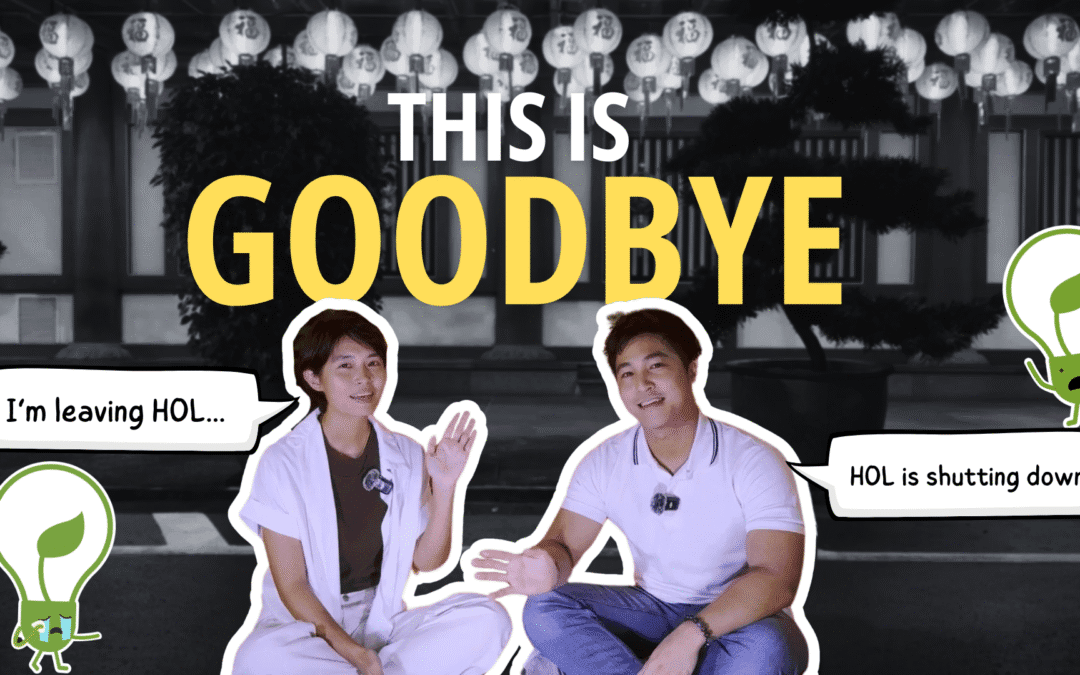

In this heartfelt farewell episode, Kai Xin shares her personal journey of stepping away from Handful of Leaves to fully pursue her Dhamma practice. Together with Heng Xuan, they reflect on their four-year journey, from HOL’s humble beginnings during the pandemic to its growth into a vibrant Buddhist platform. They discuss the challenges of parting, the strength of their team, the community they’ve built and the vision that continues beyond her departure. It’s a candid, emotional conversation about purpose, legacy, practice and trusting in what’s to come.

Full Transcript

[00:00:00] Kai Xin: I have made the decision to leave Handful of Leaves.

[00:00:03] Heng Xuan: I think we’ll shut this down ’cause like I really can’t do it.

[00:00:11] Heng Xuan: Hello. Hi. So in today’s podcast, this is where we are gonna say good goodbye.

[00:00:18] Kai Xin: So, to all our followers, I have made the decision to leave Handful of Leaves,

[00:00:24] Heng Xuan: and today’s video is gonna cover on why Kai Xin is leaving HOL. It’s not because she hates me, but more like (KX: for sure) her journey, forward, moving forward, out of HOL and what will HOL look like in the future? So in today’s podcast, we hope that we give you a better view of where HOL is going and the different ways that you can support us and support the growth of this growing community of Buddhist online content.

[00:00:51] Kai Xin: Yeah. So this is kind of my exit interview and he’s gonna roast me with questions. Let’s go.

[00:00:58] Heng Xuan: Yeah, so for context, we are actually sitting right outside the Buddha Tooth Relic temple right now. You can see it’s reddish behind us and there’ll be people walking in and out. Just shows you how popular this temple is, but we thought this is a fitting location, given how it’s kind of like a holy place in Singapore and it’s very central. Highly encouraged you guys to visit here. The vegetarian food at B1 is super good.

[00:01:18] Kai Xin: Yeah. Let’s get rolling with the first question.

Beginnings of HOL

[00:01:26] Heng Xuan: So just a recap on how we first started HOL. You can always check out the video at the end of this video on the whole journey somewhere. But essentially it was COVID period. Wanted to kind of build a directory so that people know where to go during Vesak and on a deeper level, it was because there is no online platform to kind of like capture stories of different practitioners from our time. So just about providing practical Buddhist wisdom for a happier life.

Why was Kai Xin the right partner for HOL?

[00:02:03] Heng Xuan: In short, how do I know Kai Xin’s the right person? Because I’ve been working with her many, many Dhamma projects and

[00:02:08] Kai Xin: yeah.

[00:02:08] Heng Xuan: Yeah. I knew like there’s one person that could do this with me and keep my blind spots in check. That will be Kai Xin. Yeah. So that’s, that’s, that’s why Kai Xin, long story short. Yeah.

Initial Vision for HOL

[00:02:25] Kai Xin: Oh. I remember our first conversation. It wasn’t like, okay, let’s build this together, like HOL. It was more, I think you were asking me whether I knew anyone who would be able to do something for Vesak directory. Yeah. Or like you wanna consolidate, you know, like Vesak events. And then I kind of got quite excited with ideas and then we had very deep conversation about the gaps in the buddhist scene. So from there, I think both of us had a shared vision that we really want there to be a digital presence, at least for the local community and just make Buddhism more accessible. Because usually when you are introduced to Buddhism through a Buddhist center by a friend, you have to go through all the rituals and nobody might actually tell you what you’re doing and it can be quite intimidating.

[00:03:14] Kai Xin: So I think we wanna make it easy for people to explore. And not go through like website that look completely outdated. And yeah, I think the, the vision is really practical Buddhist wisdom for a happier life and making it very relatable, which is why we share stories and yeah, we are very glad that we hold true to that vision till today.

[00:03:35] Heng Xuan: Yeah. It has been four years,

[00:03:39] Kai Xin: Wow. Yes. Four years. It’s been four years.

Favourite memory of HOL

[00:03:50] Kai Xin: Well, I have no, I have no real favorite memory per se. Okay. You go first. I, I can’t.

[00:04:03] Heng Xuan: I don’t think there is like a definite, like favorite memory. But I think it was when Kai Xin shared with me that some random person is like using HOL as a material for, you know, teaching Dhamma school. Yeah, I think that, I think that for me is a favourite memory of like kind of achieving stuff together, not… less, less of working together.

[00:04:24] Heng Xuan: ‘Cause actually we work a lot, a lot online, so we don’t really have that moment of like working at a laptop and then like working late that kind of crazy stuff, but it’s actually been very much asynchronous. So for me, that’s my favorite memory. Like I can say, Hey, someone in this country using a material for like Dhamma classes.

[00:04:42] Kai Xin: It was Malaysia actually.

[00:04:43] Heng Xuan: Yeah, it was Malaysia. Yeah. Yeah, yeah. So to me, I think that’s memorable. It felt like for the first time, I’m not just like producing content for like my friends and family to say Good job.

[00:04:53] Kai Xin: Yeah. Right. Oh, I think I know. Not so much favorite but definitely memorable. We had our first gathering and I was really, really shocked and heartened by the faces that I’ve not seen before because being in the Buddhist scene for so long, you pretty much know everyone because we kind of just rotate, right?

[00:05:15] Kai Xin: Like we go to the center and then we go to that center when there’s good talk, a good teacher in town, and being able to see new faces and people who genuinely found us through the internet or through say their friends or friends who shared a particular link, and then they started following us to then want to show up in person to check out, you know, what we actually do and to contribute ideas so that we can continue growing.

[00:05:37] Kai Xin: I thought that was pretty amazing. And there was a comment made by one of the attendees. He said, wow, I thought I was alone. I didn’t know that there are so many young Buddhists out there and what, there’s a community? And he was genuinely quite happy.

[00:05:52] Kai Xin: So I feel that we have done an amazing job in terms of connecting people. And again, it fits through the vision, not just making it accessible, but also having that, that community to support you through this journey. I think it’s something that is completely priceless.

[00:06:09] Heng Xuan: Yeah. Yeah, definitely.

Why are you stepping down from HOL?

[00:06:17] Kai Xin: So I have decided last year, somewhere mid last year, that I would like to step down from HOL. It was not a difficult decision, but also not an easy one per se. Difficult for me to actually tell him. And I suppose some people would think that I have an option to juggle my practice as well as HOL, but it was quite obvious when there are times where I meditate, yeah, and it is true, I, I would start thinking about ideas, HOL. And I think there’s another part as well. I see a very big difference in the passion and the drive. In the past I might have a lot of drive to really wanna slog it out to make an idea work, to build something. And a lot of times it’s at the expense of my formal practice in terms of time to meditate.

[00:07:12] Kai Xin: But then slowly, more and more, I just feel it’s not something that I’m willing to trade for anymore. It’s possible to find that balance, but knowing my character, it’s tough to try to do both things well at the same time. And I keep thinking about how I have access to great teachers, really, really well practiced teachers. And they’re not getting younger, younger as the Dhamma way of life. Yeah, people age and I, I too age, my parents also age, so it was quite sobering for me to reflect what do I wanna do moving forward? And I figured that money can be earned back. But time, once it’s lost, health, once it’s lost, I, I can’t get it back.

[00:07:57] Kai Xin: And this seems to be the golden window opportunity for me to just go all in into practice. And to understand how the mind works, to understand how all this enlightened masters and how the Buddha did it, to realize what they have realized. I wanna give it a fair chance, a fair shot. So I think that shift in drive, shift in focus was the main thing that pushed me to say, yeah, I don’t think it’s gonna work out.

What led to your decision to deepen your practice?

[00:08:28] Kai Xin: I, I remember quite clearly I was in an apartment. So for the good part of last year, I’ve been, I rented an apartment close to a monastery in Thailand and I wanted to deepen my practice. You know, staying close to a monastery. I can have the lifestyle of going there daily to practice in the morning, and then I learn a bit of Thai in the afternoon and do some HOL work, do some of my day job work remotely.

[00:08:53] Kai Xin: It got to a point where I remember I was working. And then I’m like, actually, what, what am I doing? I, I just suddenly felt this deep sense of I’m wasting my time and it’s very difficult for me to be doing everything all at once well. Yeah, and it, it’s not that I don’t like what I do at HOL, I love what I do and I I love all of you followers.

[00:09:17] Kai Xin: Just that in terms of, in terms of wasting time, I think there’s a deeper calling in terms of– there’s a deeper calling to want to devote my youth while I’m still healthy and able to the practice. Yeah. And formal practice specifically. Yeah. And it was slightly difficult, more to a sense where I feel selfish for doing so, but then there was a clear voice in me that told me that, Hey, actually I have been contributing to the community ever since I knew Dhamma.

[00:09:51] Kai Xin: I don’t think I have any regrets. And it’s time to start taking care of myself so that perhaps in the future I would be able to contribute in other ways or maybe through my own realization, the contribution can be deeper and more meaningful. So yeah, that’s where I kind of texted him, that was in a monastery when I was having a self-retreat. It’s like, oh yeah, by the way, I had this thought. Yeah.

How did you take the news of Kai Xin’s departure?

[00:10:23] Heng Xuan: I think it came in like waves, right? So like, I think I was like, okay, I’m gonna move to Thailand. Then I was like, I okay, okay I need to get over that. I can’t keep like meeting her in person or like, whatever. Right? So then there’s the sense of like getting over the initial loss of a friend that’s like in the vicinity and loss of like someone that you can actually meet in person. So I think that I was getting over that, that, that I was like, okay, but Kai Xin’s going like, work, work even more for HOL and like, you know, ’cause she, she was like, transitioning and like moving out the Singapore way of life and stuff. And, and then the Whatsapp came and I was like, oh my God, I can’t. I was just like, oh no.

[00:11:00] Heng Xuan: Like I can’t, can’t like do this alone. ’cause I think it’s just like you have always been able to bounce ideas and then now it’s like there’s this sudden like impending loss, I guess. The ability to like kind of just call a person at my whim and fancy and just ask random questions or like just have a certain person that you can bounce ideas with. I think definitely sad, but also at a certain extent felt happy. You’re going to Nibanna faster man, I hope.

[00:11:27] Kai Xin: Yes. I need the blessings.

[00:11:28] Heng Xuan: Yeah. Yeah. So it is that feeling, that bittersweet feeling, right? Like you’ll know that it’s the best thing for, for her as a practioner and as a Dhamma friend. Like that’s the best thing. But at the same time, there’s this loss that, well, this person is like super contributive to the Dhamma world, and she’s no longer gonna be like really there, like physically not there already. And then now it’s like virtually also not there. So I think like it was, it was really tough. Like I, I, I won’t shy away from it that I, I even told her like, I think, I think we’ll shut this down ’cause like, I really can’t do it. Like,

[00:12:00] Kai Xin: and I was like, no man, you know.

[00:12:03] Heng Xuan: I kind of like managed to go to Malaysia at that time. And I just like meditated in a Dhamma hall facing the Buddha and just like wondering, wow, what, what is the way forward? And then I was so like, full of emotions. First time I just like cry in front of the Buddha statue. I’m like, wah.

[00:12:19] Kai Xin: Oh, I didn’t know you cried.

[00:12:20] Heng Xuan: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Then my, my, my Dhamma friend like took a picture of that. But he didn’t know I was crying la. But it’s quite. But I just had to reflect on like what is best moving forward, like, and all the self-limiting beliefs that I might have, thinking that I can’t do it myself, but actually as a team and, and it’s about bringing the team forward also as well. ‘Cause HOL is more than me and Kai Xin, but really the community, the contributors that move it forward. For me, that’s, I think, quite a low point, but I think it’s like you also feel happy.

[00:12:49] Heng Xuan: Yeah. So a bit weird, yes.

[00:12:52] Kai Xin: Separation brings despair.

[00:12:54] Heng Xuan: Yes. Lamentation.

[00:12:57] Kai Xin: Well I didn’t, I really didn’t know. I think he needs a lot of assurance, so please comment and say in the chat.

[00:13:06] Kai Xin: So his wife is like this little bird that will come and tell me things, right? Yeah. And I kind of know that I knew that you were not taking it well. Um. But then I had to keep reiterating. Yeah, yeah, yeah. You know, it, I mean, you’re not doing this alone. We have a team and we have a very capable team, and in fact, I’m only doing this little bit. Yeah. So I think HOL would move on and will go on, to greater heights without me

[00:13:35] Heng Xuan: and us eventually.

[00:13:38] Kai Xin: Yeah. And if, if we are able to do that, that’s actually a really good sign because we are. I mean, the ability to decouple ourself from the organization and not having it rely a hundred percent fully, I think this is where legacies are built, right?

[00:13:53] Kai Xin: So I think over the years we have built a lot of SOPs. We have, you know, built a great team, brought in different type of skill sets and talent. Like the lady who is sitting behind the camera right now, You Shan, who’s leading the design and illustration team. And we have got many new initiatives and pillars and more people are joining us as volunteers as well.

[00:14:17] Kai Xin: So things are just gonna be exciting. And I always know that when a chapter closes, another would open. And really, you don’t know what would unfold from this. Yeah. So don’t limit yourself to thinking that HOL has to be with me or be with you. Yeah. Yeah,

[00:14:33] Heng Xuan: yeah.

[00:14:34] Kai Xin: Yeah.

[00:14:34] Heng Xuan: Yeah, she’s provided very good assurance.

[00:14:38] Kai Xin: So we are not shutting down if you continue to subscribe.

How is HOL adapting to this change?

[00:14:50] Kai Xin: We, we do have some, you know, handover plans and certain concrete guidelines or concrete steps in order to achieve that.

[00:14:57] Heng Xuan: I think in slowly having the incremental team coming together, and building out the different pillars of HOL is something that we long time overdue and having that in place was crucial to balance our mission and her transition out.

[00:15:10] Heng Xuan: So having amazing people joining our team, to support different ops, I think that was crucial in giving me a bit more confidence on where we are going.

[00:15:20] Kai Xin: Yeah, I think we also had a discussion about what are some fears and things that would create anxiety with me not being around and then working backwards from there. To say, okay, how can this not be a factor of fear? So I think there are a lot of different initiatives that we’re trying. And, to be honest, from an operational side of thing, there’s another vision about being financially sustainable, which we are still, honestly, quite far from it.

[00:15:50] Heng Xuan: Taking baby steps.

[00:15:51] Kai Xin: Yeah, baby steps. And we wanna also assure our followers that we would never commercialize Dhamma. We are experimenting with different ways as to how we would be able to either offer products or service or different things where you might pay in a professional sense or in a non Dhamma aspect. But if we were to add a Dhamma angle to make it more wholesome, would that work?

[00:16:16] Kai Xin: And we wanna keep our content free as usual, so that people would be able to access, and any bonus would or might have a price tag to it. So also hope to seek followers understanding when we do try out something that our promise to you is we would wanna stay true to the Dhamma, but you can feel free to call us out if you feel uncomfortable with certain things that the, the team is moving towards. And we need, I mean, HOL needs people to keep the team accountable. Yeah. Yeah.

What made you confident about your decision to leave?

[00:16:55] Kai Xin: I think there is, there are two aspects to this. The first one is that I don’t feel irresponsible that with my departure, the entire team would have to carry like the burden of this void. Then the other aspect is more, in personal capacity. So in terms of HOL, I’ve been seeing team members contributing amazing work and there are times where I can go on retreat where I don’t have to be contacted at all.

[00:17:23] Kai Xin: And things are just, you know, going as per usual, that brought a lot of confidence to say that hey, actually, with, without my presence, the operations would still continue. And it might not… I mean, HOL might not necessarily accelerate in terms of its growth, but at least it can continue to stay business as usual and still continue to benefit people from what it has already been doing well.

[00:17:50] Kai Xin: From a personal front, I think there are a couple of things. So, first is definitely my progress in terms of the practice. I, I feel confident, a little bit more in myself that, yeah, this is the path that I, I foresee myself, taking. And I, I don’t think I wanna back out from it. The second part is, of course, financially there needs to be some practical calculations.

[00:18:17] Kai Xin: Not to say that I’m like super rich, but enough for me to sustain a lifestyle, to focus on practice fully. Why that cough? I found a community in Thailand. And I feel very, very supported and everyone is very encouraging. I feel very inspired by their practice as well with good teachers. So it checked many boxes and the big question is just like, why wait? Like what am I waiting for? Yeah.

Are you REALLY gone?

[00:18:53] Kai Xin: So I’ve discussed with Heng Xuan that me stepping down would mean that I would no longer be involved in the operation side of things, and this means no meetings with them, no discussing, brainstorming, strategizing the future for HOL, no building stuff at all. So I would be completely hands off here, and the team has requested that I, once in a while, if there is a need for a sounding board to be contactable via call. I’ve, yeah, I, I’ve agreed, yeah, to that. In terms of frequency, hopefully not every other day.

[00:19:33] Heng Xuan: Yeah. Yeah. So, it’s kind of like a stop-gap measure, right? So if, let’s say, the team gets too crazy, like, let’s say, selling soft toys, then I think then we all like consult Kai Xin and then she’ll like, get your head screwed on.

[00:19:46] Kai Xin: Yeah. I mean, it’s not a terrible idea to sell soft toys.

[00:19:49] Heng Xuan: Yeah. Yeah.

[00:19:50] Kai Xin: But if anything that goes against the Dhamma, I’ll be, yeah, I’ll be the first to be very vocal about it.

[00:19:55] Heng Xuan: Yeah. So I think it’s just having that, keeping the lines open and agreeing, like keeping that sense of balance in check. ’cause sometimes it… we can be too stuck in the funnel and just keep tunnel visioning into something that may not align to our vision.

[00:20:08] Kai Xin: Yeah. Yeah. So you won’t see me at meetups anymore. I’m sorry.

[00:20:12] Heng Xuan: Sawadikap.

What would you miss most?

[00:20:21] Heng Xuan: Good riddance. No lah.

[00:20:23] Kai Xin: I don’t know. I, I think I’ve gotten to a stage where I try not to miss anything because there’s this, there’s this sense of attachment, right? When you miss something, when you miss something. But innately I get very excited building things. I, I like to build, I like to experiment. And of course, not experimenting alone, but bouncing it off with the team and then being able to, you know, see it from an idea to something tangible, to then getting feedback, positive feedback from the users.

[00:20:57] Kai Xin: If I have to choose something that would be something I miss. But yeah, it’s something that I have to let go as well because it strokes your ego where you receive praise and you receive the kind of validation that, hey, you know, this thing is working. Yeah. So letting go of that.

[00:21:13] Heng Xuan: Things that I’ll miss working directly with Kai Xin, I think would be the times where she says, I have a different way of looking at this, and that usually is Kai Xin’s way of saying, I disagree. Yeah. Yeah. I think having, having that, that person that openly disagrees with you is something I’ll miss. Second is I know I cannot build, in terms of technical skills, build as well as she does.

[00:21:36] Heng Xuan: So I think that’s something I’ll miss, like having that someone that you know will partner you to build something that’s pretty much crazy but possible. Like we, we build a t-shirt business out of nowhere.

[00:21:48] Kai Xin: Not, not part of HOL,

[00:21:49] Heng Xuan: not part of HOL

[00:21:49] Kai Xin: just in case you’re wondering, we’re selling T-shirts.

[00:21:52] Heng Xuan: Yeah. Yeah. So we had our own like t-shirt brand and we built out nothing. So I think like we did many random things together and I think that’s something I’ll miss, that, that, that sense of like spontaneity, that allows you to, just grow into whatever challenges that you see and you just grab and you just build, you solve it, and you just keep moving on. So I think it’s something I’ll miss. Like, not having the sounding board and not having that, that Bob the builder right next to me. Yeah.

What do you think has been the impact of your partnership?

[00:22:25] Kai Xin: I don’t know. You tell us in the comments.

[00:22:28] Heng Xuan: I think one of it is like beyond HOL is, is serving the Buddhist community, building youth groups at the same time also trying to bring Buddhist organizations more digital first. I think these are like different projects that we have done together, but I think on a deeper level is giving people the opportunity to learn the Dhamma and seeing practitioners like sprout out nowhere, through the different efforts that we have, I think that’s something like money cannot buy.

[00:22:54] Heng Xuan: Like I would imagine ourselves 10 years back the community that we had, to today, the number of people practicing the Dhamma, understanding what’s meditation retreats. I think that’s something that’s, it’s, it’s, it’s, immeasurable.

[00:23:07] Kai Xin: This is recency effect because just not too long ago there, there was a Dhamma brother who reached out and asked who, you know, put this together and whether they could ask for some inputs as to how we put together HOL and some lessons that we have learned. Then we realized that the questions actually came from a very reputable venerable in Malaysia.

[00:23:31] Heng Xuan: Senior. Yeah. Very senior venerable.

[00:23:33] Kai Xin: Yeah. Who is also trying to build young Buddhist community. I think that’s a very big gap in this area. So having signs like this that people look up to HOL or use us as a benchmark, even though, to be honest, we are not like the best or the most perfect, but at least there are some learning points that they can draw from in order to benefit their community.

[00:23:55] Kai Xin: I think that is something that is pretty amazing. And just showing what, showing, just showing people what is possible. I think for too often, too long, over the years before HOL, there were a lot of talks on ideas. We always go for these forums, this symposium to brainstorm on the next ideas and I think one thing I’m really appreciative is actually, like Heng Xuan being a very reliable partner because like for us it is like, okay, let’s not just talk. Let’s do it. And it’s very difficult to find people who is willing to put in the, the effort to actually make it work and not just, you know, say only.

[00:24:32] Kai Xin: So I hope that through our journey we have shown people that this is possible and kind of encourage them to get started. Don’t think so much, just just do and just keep it reiterating. Yeah. And just keep experimenting and see what’s there.

[00:24:47] Heng Xuan: Just fail fast. Learn fast. Yeah. And, and just have your vision in mind. But, I think oftentimes people both keep looking at me and Kai Xin’s impact right. But, it’s also important to reflect that we are also dependent on like many different generations of teachers that the teachings pass through to reach us today. So don’t just look at us like, wow. Very big and stuff like that.

[00:25:10] Heng Xuan: I, I think, important to know that we are literally just the moon and the moon reflects the light of the sun. That’s what Ajahn Jayasaro says. And the sun is the Buddha. So yeah. Always remember that.

[00:25:21] Kai Xin: Yeah. And that whatever we do, there’s a ripple effect. In fact, like for me, if there isn’t website, like Access to Insight by Venerable Thanissaro, where I can easily access sutta, discourses of the Buddha, I wouldn’t be able to deepen my Dhamma understanding and knowledge. So whatever we have today actually sits on previous generation of work, be it whether it’s online or offline. So yeah, just keep sharing, provided that you have tested it for yourself and you know that what you’re sharing, it’s, you know, aligned with the Dhamma. Just keep practicing doing good work.

What excites you most about this new chapter?

[00:26:05] Kai Xin: I am not really excited about anything, nor am I really looking forward. I think I’m just taking things one step at a time, and as it comes, life will be pretty boring ’cause I’ll be doing the same routine every day. I suppose I would just keep putting in the effort and, maybe what excites me is to be closer to the Buddha in a sense where I get to practice what he teach.

[00:26:28] Kai Xin: And I think that’s the closest distance you can get to him. Right? Yeah. And by putting my best effort to realize the teachings. Recently we did an interview with Ryan, who, our, our friend, Dhamma friend Ryan, who is now a monk. And when I asked him how he felt. I think it encapsulate how I feel as well and the word is “relief”.

[00:26:51] Kai Xin: And he explained because this is something that he is been wanting to do for such a long time, and he finally is able to put things down and don on the robes. I, I’m, I’m not gonna don on the robes, just a disclaimer. But I, yeah, I, I think instead of excitement, it’s just this sense of relief to say like, oh, it’s finally here.

[00:27:08] Kai Xin: Because for such a long time, even when I first started working, people ask me how’s work? And the answer would always be, it’s great. But then there’s this lingering thing that I, I’m not sure what it is, but something just feels off from the center point, like from the true North and yeah. Now things just feel in place like it’s aligned finally. So it’s not boring.

You Shan: What’s the boring routine?

[00:27:33] Kai Xin: Boring routine. So you would pretty much wake up 4:00 AM in the day, monks wake up at 3:00 AM. 5:00 AM chanting. And then you help out with chores, sweep the leaves, clean the tables, and then there will be almsround You can help out with that as well. There’ll be more chanting in the morning at about eight o’clock.

[00:27:54] Kai Xin: Have your main meal. We only eat once a, once a day. One main meal a day. You have pretty much the whole day to yourself until 3:00 PM chores again. And then in a monastery that I’m in, 7:15 PM it is another evening chanting session. Yeah. And every day it’s just the same. There might be projects in between

[00:28:15] Heng Xuan: and festivals.

[00:28:16] Kai Xin: Festivals, yeah. Which, when the monastery can get really busy, we’ll have to do with cleaning and yeah. Like planning, organizing. Yeah. I guess the only difference is if you’ll meet different people maybe on a daily basis, because people come and go, our visitors and retreatants. Yeah.

[00:28:32] Heng Xuan: So I think what excites me most is the expanding reach that HOL is having and having more people on board. Contributors that join the team would ensure that we bring even more human capital into the Buddhist world. And where I’m excited at one of the different ideas is to upskill the Buddhist community to get even better at doing what they do.

[00:28:52] Heng Xuan: And I believe that HOL will be well positioned to help that. Other areas would include exploring new formats to reach people. And already we do see many different people coming to Dhamma through different articles, through different videos and podcasts. So for me, I think that remains a really exciting area for us to keep experimenting because the moment you stop experimenting then it’s like you’re not trying.

[00:29:16] Heng Xuan: So it’s, I’m looking forward to more failures, kind of. Yeah. And, and just keep learning, like we said, no to merchandise, but like maybe that’s gonna come out for us. So for me, that’s what excites, is to never say never and just keep exploring where things go and meeting super cool people, like that are joining our team. I don’t shout out individually, but like yeah. You know who you are. Yeah. You all know who you are and really talented in what you do.

How will your friendship evolve?

[00:29:40] Kai Xin: We’ll still be friends. I’ll still be kind of contactable, just not as accessible for me, I think it’s a big question mark because it’s never the same or never gonna be the same as compared to you being able to meet up, you know, chat over meal and bounce off ideas.

[00:30:06] Heng Xuan: I think I have to meet her in Thailand, so I have to go Thailand. I think it’s just, I mean your friendships on maintenance mode, just like when I go Thailand then I’ll see her. And somehow I just keep going to Thailand. I dunno why, but yeah.

Words of wisdom for the team and future contributors?

[00:30:23] Kai Xin: What advice? What wisdom? Wisdom. Oh wow. Wisdom. Even worse, I don’t have any innate wisdom, so I have to lean to the Buddhist words. I think one thing that never fails so far based on my own experience is to use the three poison as yard sticks. It gets a little tricky when we wanna embark on a new initiative because you might not know whether it is fulfilling your alter ego.

[00:30:51] Kai Xin: Is it serving the community? It could be, but there can also be a very fine line or a trace of unwholesome. Because I think financial sustainability is always very tricky, and that’s like a hurdle that we are trying to cross as HOL collectively. So greed, hatred and delusion. These are the three poisons.

[00:31:09] Kai Xin: If we can, the team can kind of check against this to see what is the level of greed, hatred, and delusion. Delusion is hard to to check, so have someone keep the team accountable. I think pretty much the team will do. Okay. Yeah. ’cause the last thing that personally I would want for any Buddhist organization is to go off path when we might start off with a very wholesome intention, with a wholesome vision, but, you know, we get blinded by all of this, blinded by our own defilements. So yeah, have that as the yardstick. I think that would be the safest bet. Not, not really a bet, but a safest route. So words of the Buddha.

Final words to each other

[00:31:58] Heng Xuan: It is kind of sort of the end, but not the end of a journey that we have been embarking since we were 17.

[00:32:06] Kai Xin: Wow. Yeah, wow.

[00:32:07] Heng Xuan: Like it has been, yeah, it has been a good like 15 years working together and things are gonna change. It’s going to, it’s just gonna be different. We’re not gonna build stuff together anymore.

[00:32:17] Heng Xuan: So I think that’s really different, but I just wanna thank you for all the random shit that we have done together, like for the past 15 years, which is like almost half of our life, like almost half our lifetimes. Right. Just doing projects together. So, yeah, I just wanna say I could think of no better person than to build this entire ecosystem with together. So thank you.

[00:32:36] Kai Xin: I’m getting emotional. How can I hug you? Aw, you know, the first episode of podcast I cried too, because Cheryl made me cry. Yeah, I mean, I’m very appreciative. Yeah, I, I don’t know. I always feel like there’s a lot that you can do as a person and like for to you individually, apart from all the thanks, is, is really, you don’t necessarily have to take everything on your shoulder by yourself.

[00:33:10] Kai Xin: I think sometimes it seems scary because it can feel like you’re walking alone. Mm-hmm. But you have people around to support and even though you’re great at doing a lot of things, often better than others, sometimes it’s okay to lean on others even though they might not necessary, be it the a hundred percent, you know, level.

[00:33:31] Kai Xin: Yeah. ’cause when you have a community, you have many, maybe like 75% of people, and that way surpass a hundred percent in the, as an individual. So don’t be too hard on yourself and you don’t always have to be productive. It’s okay to sometimes, you know, go on a break. Yeah. And not think about HOL. Give yourself permission that, give yourself permission to do that.

[00:33:54] Kai Xin: And yeah, don’t always have to, yeah, do things for others. I know you do a lot of things for yourself, but, at the back of your head you’re like, Hey, how can I milk this? Yes. For HOL, for DAYWA, for whatever, you know, initiative and just, you know, productivity kind of guy, but it’s okay to not be productive sometimes. Yeah. And just let your mind rest. Aw. Are you crying?

[00:34:23] Kai Xin: But I am really thankful. So I kind of feel like we have been doing, we’ve been like been doing this, contributing to Dhamma for like multiple lifetimes. Yeah. So for me,

[00:34:35] Heng Xuan: see you for seven more lifetimes.

[00:34:37] Kai Xin: Yeah. This is not really goodbye. You’ll still see me, come to Thailand. Give you an excuse, a reason to come to Thailand for retreat. Yeah.

[00:34:52] Kai Xin: Like, subscribe, support.

[00:34:58] Heng Xuan: Yeah, I think that’s, that’s really it, like contribute our efforts and contribute our skills. Okay. Take that again. So, like, subscribe and share this video. But jokes aside, I think contribute your skills. If you feel like there’s something that you always wanted to try, experiment, just try out.

[00:35:16] Heng Xuan: Just reach out to us and share with us, like, why do you think this is a fit for HOL? We’ll work something out. I think we are always looking for people with the skill sets and expertise to bring things forward. Oftentimes we put a hundred percent of our work life energy right into just our careers. But why not put a bit of that percentage of that innovation, that knowledge into serving the Dhamma? And I think that will bring immense benefits.

[00:35:40] Kai Xin: And as you talk about financial sustainability, we, the team is, is really bootstrapping. We’ve just recently hired or experimented with hiring a full-time content editor, not so sure about how this experiment goes, but if we have the capital we can, or the team has more room to play around with ideas and to execute on certain things. So if you have been benefiting so far, it would really, really benefit not just the team, but the entire community, because the team is not doing this for the team’s sake.

[00:36:12] Kai Xin: We are doing this for everyone’s sake. So yeah, go to the Patreon or sponsorship page to see which one kind of appeals to you? Mm. I think beyond supporting through monetary means, of course, it, it’s really supporting through your practice, by being a good practitioner. It really has an immense effect to the people around you.

[00:36:35] Kai Xin: People will start feeling like, Hey, something is different about this. Like, oh, I read HOL article, oh, because of HOL you know, I go for this retreat and stuff. So work on yourself. Yeah. And that’s like the best marketing and publicity one can do for Buddhism. Yeah. Yeah.

[00:36:48] Heng Xuan: Yeah. I always say don’t be the proverbial like auntie who says they do the Metta chanting then after that hit and kill the mosquito. Don’t, don’t be that person. Right. Just go and practice. Be a impact. Fly the flag of the Buddha way, way, way high. And I think that would be crazy, crazy good to this world.

[00:37:07] Kai Xin: Yeah. And for yourself too, in case you don’t make it this lifetime, next lifetime dhamma will still be around.

[00:37:11] Heng Xuan: We hope that you enjoy this series on exploring why Kai Xin is saying goodbye.

[00:37:16] Kai Xin: Yeah. And

[00:37:17] Heng Xuan: we will see you soon.

[00:37:19] Kai Xin: All the best to everybody. May you stay happy and and wise.

Buddhist Youth Network, Lim Soon Kiat, Alvin Chan, Tan Key Seng, Soh Hwee Hoon, Geraldine Tay, Venerable You Guang, Wilson Ng, Diga, Joyce, Tan Jia Yee, Joanne, Suñña, Shuo Mei, Arif, Bernice, Wee Teck, Andrew Yam, Kan Rong Hui, Wei Li Quek, Shirley Shen, Ezra, Joanne Chan, Hsien Li Siaw, Gillian Ang, Wang Shiow Mei, Ong Chye Chye, Melvin, Yoke Kuen, Nai Kai Lee, Amelia Toh, Hannah Law, Shin Hui Chong