TLDR: What can we do when we are thrust into the role of a caregiver? In Singapore & Malaysia, we are taught to be filial. What does that mean when our parents are sick? What can we do?

What do you say when your mum tells you that she’s going through too much, and she doesn’t want to suffer anymore?

Her body is breaking down right in front of our eyes. It happens gradually, but at times, the deterioration is sufficient to catch us by surprise. It baffles me how she can have such poor control of her legs. Why can’t she take a bigger stride? Why is her body awareness so bad?

We’ve been told that we don’t own our bodies and that everything is impermanent. However, it wasn’t until now that this message hit home.

My mum has Parkinson’s disease and a heart condition. Last year, she was diagnosed with cancer. You never expect these things to happen to you or your loved ones. And sometimes I wonder why these things would happen to such an incredibly kind person.

Loss

Watching my mum lose her health has been hard.

There is a loss of motor function, cognitive decline, and also emotional changes associated with the disease. As a family, we are learning to navigate these changes skillfully. It isn’t always pretty.

I found myself ugly crying on the MRT a few days after my mum’s cancer diagnosis. I remember feeling pangs of fear and regret, but there was also this underlying sense of loss. I’ve always had this idyllic picture of what the future would look like for our family.

I envisioned a healthier version of my mum celebrating various milestones together, playing with my kids, and doing the things she loves.

With these diagnoses, I felt robbed of this version of the future. But this is the problem isn’t it? The attachment to ideal states and a built-up fantasy of reality.

As a patient, there is a loss of independence, loss of vitality, and loss of identity. As a carer/ family member, we lose the person we used to know, as well as the future that we had envisioned for ourselves, and to some extent, freedom.

The non-acceptance of what is.

I was watching mum get into a car one day with so much effort and difficulty, I was in disbelief. I remember deliberately not helping her and thinking to myself, “Surely it’s not this bad. She has to be able to do it on her own”. I refused to believe that her motor skills would decline just like that.

Another time, we were trying to walk across the mall to a restaurant, and it was the most laborious process. At one point, we were at a standstill because she couldn’t get her legs to move. It was a very difficult moment.

As my mum’s condition progressed, I found myself being more impatient around her. I would say things that would upset her and lack empathy for what she was going through.

I was aware of the unskillful states arising, but my mindfulness was not strong enough for me to snap out of it. It was very confusing because I knew that a good daughter should be patient and caring in a time like this, and I wasn’t. There was a lot of anxiety and guilt.

It took me a while to realize that the anger was not directed at her, but rather, towards the reality of things. There was a lot of resistance and anxiety due to change. I was so attached to the person she used to be, and I wanted things to remain that way.

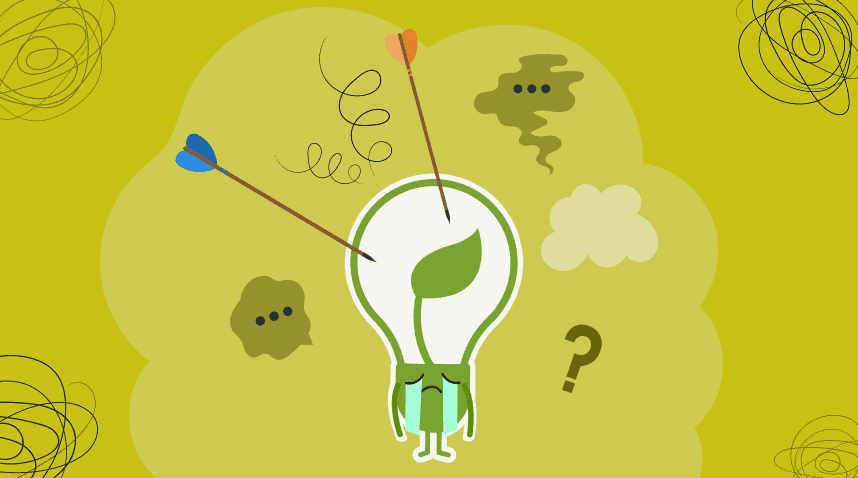

Avoiding the second arrow

The Buddha talked about avoiding the second arrow – creating suffering out of the unpleasant experience. My mum’s condition is the first arrow; and my aversion, sorrow, and distress in response to it is the second arrow.

I am suffering because my mum, whom I love very much, is suffering. I am caught in aversion because I don’t want to see her in this state. However, it ended up creating more suffering for both of us.

Ajahn Kalyano, a wise monk based in Australia, mentioned in one of his talks that we need to back up our metta with equanimity and treat our suffering correctly. While we can’t control the first arrow, the second arrow, which is our reaction to the first, is optional.

It’s okay.

The best advice I received whilst dealing with all of this was, “It’s okay”. It was so simple but brought me so much relief. It is a difficult situation, and it is okay to not know how to respond skillfully.

This predicament uncovered the dark corners of my mind and it was not pleasant to watch. I had a hard time reconciling with myself.

It took some time, but I learned to be kinder to myself and to forgive myself. It was when I started doing so that I had the spaciousness in my mind to investigate what was going on. Being able to see things more clearly has helped me in my relationship with the situation and my mum. For anyone going through a similar predicament, I want to let you know that it is okay.

Establishing mindfulness

Situations like these do require more endurance and forbearance than what is normally required of us. Ajahn Anan said that we need to put effort into establishing mindfulness, and making our samadhi firm so that we know what the mind is like.

It is normal for anger, fear, and delusion to come up in situations like these. But when these unwholesome states do arise in the mind, we need to put in the effort to skillfully abandon them.

On days when it gets overwhelming, take a rest, do some chanting, meditate, establish samadhi, and bring up endurance once more.

Looking impermanence in the eye

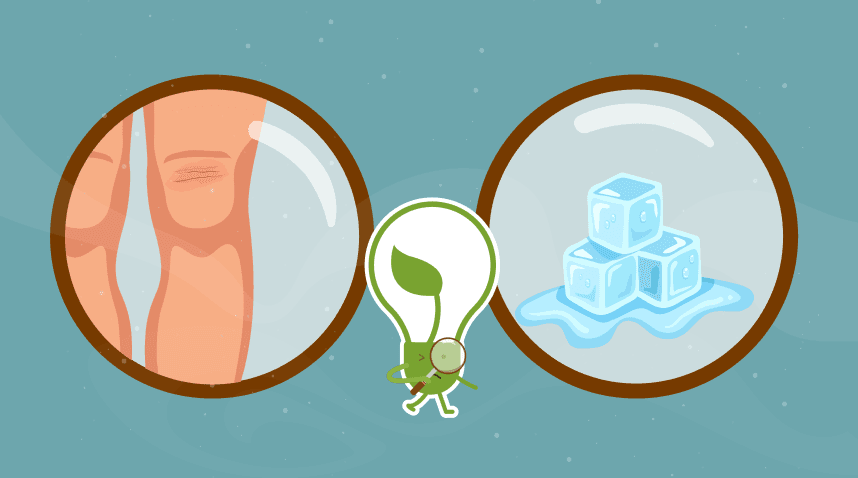

I was uneasy the first time I had to clean my mum’s surgical wound. It wasn’t the sight of the wound that was hard to look at but the empty space that was once a lump of muscles and tissues.

Seeing the stitches and scar tissues in place of it was to have a good look at the impermanent nature of things. It left me contemplating how something once considered our ‘self’ or a part of us, can be cut away and disposed of simply as medical waste.

No matter how hard we try to hold on to these conditioned phenomena that we once thought to be pretty, strong, and delightful, they are all subject to decline. Ajahn Chah, a famous thai forest monk, said that we are ‘lumps of deterioration’. The body declines just like a lump of ice. Soon, just like the lump of ice, it’s all gone.

The drawbacks of the sensory world

This has truly been a huge teaching moment for all of us: about impermanence, suffering, and nonself. As a Buddhist, these words get thrown around so much that it becomes trite, but it is moments like these that definitely drive home the point. Everything we have in this world is borrowed. We have them for a while, then it has to go.

Wise Steps:

- Know that it is okay to not be okay in such situations, we need patience more than ever. For both ourselves and our loved ones

- Don’t take health for granted. Be present with your loved ones because you don’t know how long your or their health will last

- When was the last time you noticed impermanence in your life? Peeking into the reality of things daily can cushion our minds when things go south.