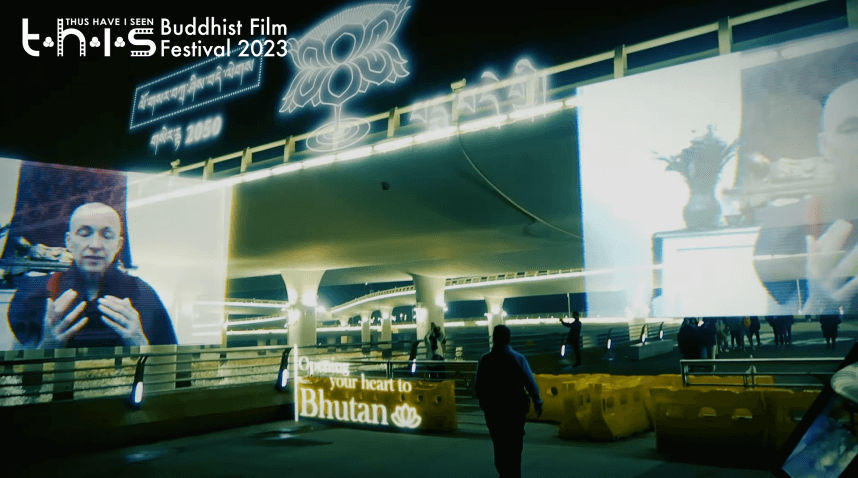

TLDR: How would a conversation about Buddhism from three different perspectives (a Professor of Asian religions, a Zen monk and a Tibetan nun) turn out to be? Will we wake up in 2050 seeing true happiness?

*NOTE: This contains Spoiler for the film Waking up 2050*

In a world where technology and materialism often take centre stage, the quest for true happiness becomes even more elusive. Waking Up 2050 is a thought-provoking documentary that takes us on a journey to explore a common understanding of Buddhism from varied angles and its relevance in our ever-changing world.

Directed by Ray Choo, this film offers diverse perspectives from individuals living with Buddha’s teaching or learning and teaching it (Ani Pema Deki, Kodo Nishimura, and Prof. Daniel Veidlinger) shedding light on the profound teachings of Buddhism and its potential impact on our lives.

The documentary seems like separate interviews merged into a film without the questions asked out loud, an interesting structure as the viewers could still understand what the interviewees are referring to. The futuristic visuals serve as an additional anchor for contemplation with the presence of the director is cleverly noted in narrations throughout the film, gently steering the topics for the viewers.

Labels

Labels are often used for practical reasons, mainly as a point of reference in communication with others. We need a common term (e.g. a person’s / object’s name) for a conversation to be as effective.

Prof. Veidlinger teaches Asian religion at the University Chico and is often asked by students about the definition of Buddhism.

“Whatever people call it, I don’t know and I don’t very much care what it’s called”

Prof. Daniel Veidlinger

Let’s investigate: what is Buddhism, in conventional meaning and its true meaning? Some may define it in the rituals, some may define it as philosophy, others may categorise it as one of religion, or even differentiate it as spirituality.

What does being a Buddhist mean to individuals and society, and its true meaning? Or is ‘being a Buddhist’ what we need/should strive for?

Buddha said ..you don’t deserve the label ‘outer robe wearer’ just because you wear an outer robe

‘Outer robe’ represents a perception. How much does perception of oneself and others affect our definition of the surrounding world, including how we interact with that surrounding world?

Kodo Nishimura, a Zen monk who also dresses up and works as a make-up artist – is he fitting in the definition of ‘monk’? By whose definition? Would Lord Buddha approve of this choice?

Interestingly, monastics in Japan underwent a fundamental change from Buddha’s Vinaya (monastic rules). There were records of monks getting married during the Kamakura period (1185-1333).

However, the further secularisation of monastics for some sects was cemented in 1872 which allowed monks to be free to “eat meat, take wives, and shave their heads” as they chose.

Scholars suggest that allowing monks to marry was a ‘necessity’ to allow the continuance of inherited temple land to be passed on. The taking up of jobs beyond being a monastics was also done to fund their livelihood as some temples did not receive enough donations for day-to-day living.

Hence, this film might bring some form of cognitive dissonance for viewers who are used to monks being celibate and not in the ‘business’ of running temples. However, viewed through the lens of Japanese contemporary Buddhism, this is more rule than the exception.

Dhammapada 266:

He is not a monk just because he lives on others’ alms. Not by adopting outward form does one become a true monk

When Kodo Nishimura was uncertain whether he was disrespecting Buddhism by also being involved in the fashion industry, he sought advice from his Master and strengthened his conviction in his choice.

“The Master said if the message can be delivered to many people and you can spread it easier, I don’t think wearing something shiny is a problem”

Kodo Nishimura

The notion that monks are still involved in worldly roles (e.g. taking up occupation), even if the intention is to expand Buddhism and draw more laypeople to be interested in the teaching – would’ve been something beyond the concept of ‘monastic’ to me. However, when applied to how Buddhism has developed in Japan, this brought me to a greater understanding and how perceptions can differ by magnitudes when history & culture intersects.

Even though his views differ from my personal opinion, I found it helpful to not be overly attached to how a monk should behave in this film and instead just let that disagreement sit peacefully within me.

Japanese Honen Buddhism, Bhutanese Vajrayana Buddhism, and Thai Theravada Buddhism – are these conventions created by the mind? What are the benefits and drawbacks of such segregation and categorisation?

“The Dalai Lama often says Buddhism is religion, philosophy and science”

Ani Pema Deki

It seems to be a much deeper assessment than simple external perception. How many of us have genuinely adopted the full teaching to pass judgment? Or rather, would it still matter when one does reach such a level of realisation?

It feels like the effort to clarify such conventions may be less relevant to me, than using the same effort to take on the practice – of which the clarity would most likely arise from the journey.

Light of Asia

A monk asked Seigen,

“What is the essence of Buddhism?”

Seigen said,

“What is the price of rice in Roryo?”

Buddhism is often linked to Asia. In Southeast Asia where it is one of the major religions, many follow traditions that could be considered cultural practices (e.g. 7th lunar month prayer or praying to gods in general).

Where does culture and Buddhism meet? A way of life or a teaching? When those in Asian countries do things ‘a Buddhist is supposed to do’, does that make us a Buddhist?

“..if one sees the core Buddhism as a self-transformation, conquering desires.. to emerge into a more enlightened mode of thinking.. seeing the world as it is.. realise they’re impermanent – then the vast majority of Buddhists are not really practising. .. Though the essence of Buddhism is that there is no core that doesn’t change”

Prof. Veidlinger

Is there a benefit to an outsider’s mind looking at these practices and rituals to understand Buddhism? Is it a practice done in a specific place/time or can it be part of life? Embedded into our mindset, habits and values.

On the other hand, the female monastic topic has been an ongoing conversation. Ordination for female monastic is not allowed in many Buddhist lineages due to some scholars arguing that since the nun’s order died out long ago, it should not be restarted.

Restarting it, they argue, requires breaking the rules set down by the Buddha which required the presence of already fully ordained nuns. Hence, this creates a circular argument which cannot be easily resolved. For some who do, it isn’t at the same level of recognition as male monastic and with more rules applicable to females than males.

Emma Slade was ordained in Bhutan, taking the Buddhist name Ani Pema Deki. And because she has had a child, Ani Pema Deki feels that her ordination is the result of luck. Nevertheless, she feels the experience of caring for her child, a vulnerable being, with patience and love has helped with her practice.

“It is real combination and it’s very useful for the path”

Ani Pema Deki

When we ask ourselves, what is the reason I’m following this teaching? What has arisen for us: because that’s how it is with my family/society, or because I choose to follow the path from my understanding.

For many (including myself), it could start as automatic family/society culture and evolve into intentional choice from the ground of clearer understanding – which can be a path of its own.

Happiness in the world and beyond

The mind that is bent on finding meaning (or ‘happiness’ as it thinks), defining what’s right or wrong according to convention – seems like a turning circle with no end or rest. Similarly, the intention to present what is thought to be ‘perfect’ to the external world, is futile.

Amongst diverse worldly experiences packaged to bring happiness in the progressive world, will we wake up to true and lasting happiness when we arrive in 2050?

The next time we start a conversation with ‘I am..’, how would we continue the sentence? When we ‘do’ Buddhist instead of ‘be’ Buddhist, that’s probably a reminder to investigate the intention behind it.

At the end of the day, which is the more important question? Is the label used to refer to happiness or the actual path to arrive at true happiness?

“The teaching of Buddha-Dharma is limitless and boundless”

Narrator

Conclusion

In a world filled with uncertainty and rapid change, Waking Up 2050 aims to shed a guiding light, and illuminate the timeless wisdom of Buddhism and its potential impact on our life, today and into the future. As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, the teachings of Buddhism offer solace, inspiration, and a roadmap to true happiness. Let this documentary catalyse self-reflection and a source of hope as we strive to awaken to our fullest potential.