TLDR: In the second part of our pilgrimage series, Tate Aung acquires a symbol, a wooden Buddha rupa. She experiences a pivotal moment of renunciation by giving away a prized possession, exemplifying the importance of relinquishing attachments for spiritual growth. Next, Angela Tan’s contemplation on death during a Ganges River cruise in Varanasi leads to profound insights on life’s impermanence and the cultivation of of virtues in pursuit of liberation.

You may read Part I right here!

Introduction

Going on a pilgrimage often brings us to some unexpected realisations and experiences. In this second instalment of our three-part pilgrimage series, we delve into two reflections by two fellow pilgrims, Tate Aung and Angela Tan as they navigate the paths of renunciation (Nekkhamma) and death contemplation (Maranasati) amidst the sacred landscapes of India.

From the pursuit of generosity to contemplating life’s impermanence, their narratives offer some poignant insights into the essence of spiritual growth and the pursuit of enlightenment.

Nekkhamma by Tate Aung

In the serene setting of Rajgir, a town in the district of Nalanda in Bihar, India, I made a significant acquisition – a beautifully carved wooden rupa made of wood from the sacred Bodhi Tree.

This rupa of Lord Buddha in his most austere state of renunciation was to me a symbolic reminder of the suffering the Buddha felt, along with his unwavering determination on his path to enlightenment. Reflecting on my disposition, characterised by what I perceive as a lack of Viriya (effort) and a tendency to procrastinate, I had wanted to place this rupa in my home as a stark reminder to infuse more effort into both my spiritual practice and work life.

The journey of this rupa did not end with its purchase. I carried it to the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya, where it received blessings at the Buddha Metta statue.

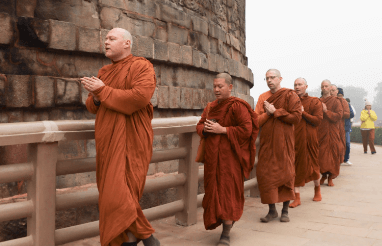

It then further continued at the deer park in Sarnath where the Buddha first proclaimed the Dhamma to the world.

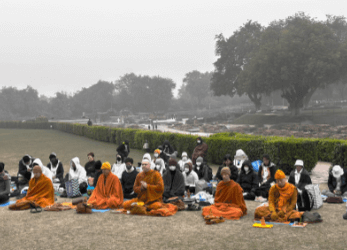

While our group circumambulated with the rupa around the stupa (commemorative monument) at the deer park, the recited teachings of the Dhammacakkhapavathana Sutta and the Anatta-lakhana Sutta from ~2500 years ago echoed in the air. I would think that layers of blessings were bestowed upon the wooden rupa.

I had brought along another rupa on the trip to the deer park to offer to Kruba Joe, a monk accompanying us on this pilgrimage. However, while everyone was meditating, I became quite distracted and was in a deep dilemma on what to do when I saw that the rupa intended for Kruba Joe had a small crack at the back.

As good as my intention was to give it away, I could not unsee the crack on the rupa’s back and thought how “less-than-beautiful” it was when compared to the other rupas gifted to the other monks who were around.

Right then, I recalled the goodness of my dear kalyāṇa-mitta (spiritual friend), Kaylee, who previously gave a singing bowl to Phra Danny (despite her initial desire to keep it for herself…)

Inspired by her example, I too decided to give away the “ultra-blessed” Austere Buddha rupa intended for myself to Kruba Joe. Honest to Buddha, the Austere Buddha rupa not only had very good craftsmanship but also cost twice as much, hence I did feel the pinch and was quite unwilling to part with the rupa, and more so, the blessings associated with the rupa.

Oftentimes, most of us only give away things we don’t need, and things we don’t find difficult to give away.

You could say that I was delighting in the pleasant sense-object like the rupa, and growing a dangerous attachment to it that could cause me some suffering over it in the future.

Hence, the act of giving away a prized possession became an expression of renunciation, serving as a reminder to not only give away what is easy but to part with what is most difficult (which includes renouncing our defilements).

On the topic of renouncing our defilements, while I was at Rajkir, Bihar (prior to reaching Uttar Pradesh), I had indicated to my dear kalyāṇa-mittas (spiritual friends) that yes, I would be taking the Eight Precepts, and hence would not be eating after 12:30pm.

Yet, the allure of an exquisite buffet upon arrival at our hotel in Uttar Pradesh tested my commitment. Succumbing to temptation, I found myself on the brink of breaking my precepts during this pilgrimage. In a moment of intervention, a wise kalyāṇa-mitta, Heng Xuan, gently told me off by mentioning that “..breaking your precepts is very bad kamma…. you said you were going to take 8 precepts”. He also said something along the lines that it was bad for my “Sacca Parami” (transcendent virtue of truthfulness) too.

That stopped me in my tracks.

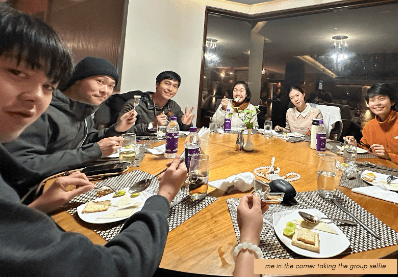

This timely piece of advice halted my wavering, and I chose to recommit to the precepts, a decision we celebrated as a team, captured in a joyful photo with the entire DAYWA group observing the eighth precept successfully.

The conscious and intentional act of stepping away from temptations which lead us astray from our commitments is a powerful act of renunciation.

In essence, this entire pilgrimage served as a powerful reminder that every action we undertake is a fuel for our Parami (Virtues). The habit to renounce not just material possessions but also our inner defilements, such as tanha (craving), becomes crucial in propelling us forward on the raft towards the shores of Nibbana.

Maranasati (death contemplation) by Angela Tan

Witnessing the four sights of ageing, sickness, death and an ascetic, the Buddha sought a way out of suffering. On this pilgrimage, the sight of death (through viewing cremations happening right before our eyes) was a particularly impactful one.

After days of meditation and visiting holy sites, we were treated to a cultural experience; a cruise on the Ganges – one of the most sacred rivers in the world.

Prior to boarding the Ganges cruise, we learnt that some Hindus believe that people who die in the city of Varanasi can achieve moksha (liberation). As part of their death rituals, some Hindus cremate their deceased relatives at a famous ghat (defined as: a level place on the edge of a river where Hindus cremate their dead.) Then, their ashes are put into the Ganges river where some Hindus believe that the deceased can reunite with their god Shiva.

As we boarded the cruise and headed for the famous cremation ghat, I could not help but anticipate sadness. I carried with me some preconceived notions of death – in Chinese culture, death rituals are often associated with a sombre sense of loss and heavy feelings.

Upon disembarking near the cremation ground, my eyes were indeed filled with tears – from the fumes of five recently deceased bodies burning all at once! When my watery eyes cleared, I saw family members of the deceased surrounding the fire, looking at ease with where they were and what they were doing. It was nothing like what I expected. There were no tears, no wailing, an absence of distress.

On the contrary, there was a sense of acceptance. And I was not the only one who felt this. Later on the way back to our evening rest, other pilgrims shared the same sentiments too. Death, to the Hindus, is a natural part of life. This is part of the notion of “Right View” expounded by the Buddha.

This experience led me to reflect that no matter your situation, whether you are rich or poor, happy or upset, sick or healthy, death is inevitable. It is a short sprint between life and death.

What matters most is to continually do good, give generously, learn earnestly, forgive steadfastly and patiently cultivate.

The next day, contemplating this experience about death allowed me to have a joyful meditation session. I was able to disengage from my ever-planning mind and enjoy the present moment, one breath at a time. Having returned from the pilgrimage, I continue to practise death contemplation whenever I walk past funeral services.

Conclusion

As we draw the curtain on this chapter of contemplation and revelation, both Tate’s and Angela’s stories shed light on the intricate journey of spiritual growth while seeking enlightenment. From Tate’s journey of renunciation, marked by the relinquishment of material attachments to Angela’s profound contemplation on death and impermanence, their encounters remind us of the transient nature of existence and the urgency to cultivate good virtues that aid us to liberation.

May their insights inspire us to be more determined in our spiritual practices, guided by the light of wisdom and the aspiration for Ultimate Happiness and freedom.

Wise Steps:

1. Reflect on material (or mental) attachments: Take time to identify attachments to material objects and contemplate the possibility of letting them go for a better cause, understanding that renunciation can lead to spiritual growth and a lessening of our attachments . The same could apply to our mental attachments – to objects, experiences, views and perspectives.

2. Embrace impermanence (anicca): Contemplate on death regularly to cultivate our acceptance of life’s transient nature and prioritise actions that contribute to spiritual development and well-being. Regular reminders on impermanence also provide us with a sense of urgency to practice.