TLDR: To love and care without attachment, one must let go and realise that nothing is truly ours.

“I discovered a great spiritual example at the supermarket!” declared Āyasmā Rāhula on a cold rainy night in December.

I was at the Singapore Buddhist Mission on a Wednesday night for a special dhamma talk by the Mexican-born, Burmese-ordained monastic.

He was giving a talk titled, “How do we care and love without attachment?”.

We often learn that to attach is to set ourselves up for eventual dissatisfaction. So is it possible to care and love without attachment?

I’d previously been exposed to Bhante Rāhula from a YouTube video shared with me by a dear friend from RainbodhiSG and was delighted to discover that he was similarly animated in real life as he was online.

At the start of the talk, he told us to put on spiritual safety belts, for he was going to take us on a journey that might get a little rocky.

His talk was divided into 3 main parts.

Mettā and letting go of my crushes

He began by exploring what mettā (translated into English as “loving-kindness”) was.

The characteristic of mettā is to promote the welfare of all living beings, he explained.

Mettā’s function is to prefer for the welfare of others and oneself. Its manifestation is the removal of ill will.

Finally, the proximate cause of mettā is to see beings as lovable, and not have selfish affection.

Love, he continues, makes you feel content. Attachment, however, makes you suffer.

That struck a chord.

All my crushes were causing great suffering.

I had to let them go. If nothing else, I think I had already benefited from the first third of the talk.

An analogy might be in order.

Imagine a girl holding a heavy sack of rice weighing about 5kg. For a long time, she carries it around wherever she goes. This sack of rice is precious to her. Even though it weighs her down, she holds it close. Eventually her arms get tired. She reluctantly puts it on the ground. She lets it go.

I was that girl. My crush was that sack of rice.

In my mind, I laid the sack of rice down, my crush, on the ground.

I was fine with or without her.

It was alright.

This mental letting go felt freeing. A weight lifted. My mind was lighter. Clearer.

Of course, this letting go is a continual process. For the default action is to hold the sack of rice close to the chest. The girl has done it for so long, that is her natural state of being. Every time she is aware, she puts the sack of rice down, she lets it go.

So it is with my mind. Again and again and again, I make a mental shift, and there is a felt sense in my mind to let the crush go.

He told us that with attachment to a person often comes worry and jealousy leading one to exert control over the other, and ultimately violence, whether verbal or physical toward the other party.

I recalled breaking up with my very first girlfriend mainly because I felt very suffocated due to the extent of control she was exerting over me.

Letting go, Bhante explains, helps both you and your partner to be free.

Freedom. That’s what so many of us seek.

The difference between desire and attachment

The excellent spiritual example Bhante Rāhula discovered at the supermarket went a bit like this.

Imagine we wanted to eat some potato chips. We go to the supermarket and pick out a bag, sour cream and onion potato chips. We put it into our shopping basket and proceed to the checkout.

At this point, is the potato chip ours?

No, it belongs to the supermarket.

If we were to rip open the bag to eat the potato chips, the security guard would reprimand us and tell us to pay before consuming the product.

At the checkout, the cashier smiles at us and begins scanning the items we have picked out at the supermarket.

At this point, as she scans the items, do the potato chips belong to us?

Nope.

They still belong to the supermarket.

Finally, after the scanning is done, we pay with our card.

Beep.

Now, the potato chips belong to us.

If the cashier decides to open the bag of chips and eat it, you’d probably yell at her and say, “Hey! That’s mine!”

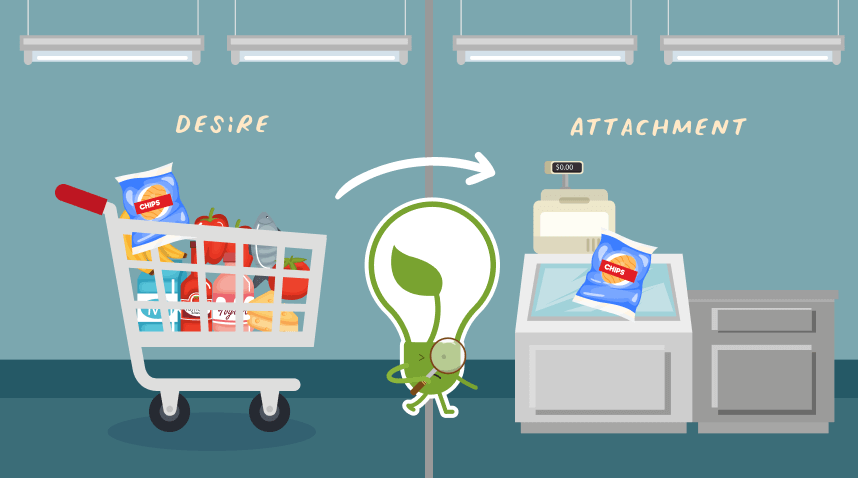

That is the difference between desire and attachment.

Before payment, the potato chips was just something we wanted. After payment, the potato chips became “MINE”. Attached to me.

Desire is when something is just a feeling, a want of a project, a thing, or a person. When it transforms into attachment, we then think, in our mine that this project, this thing, this person – “IT IS MINE”, when it really isn’t.

In a split second, after we pay for the potato chips, it is “MINE”.

Wow.

I then began to realise that often, it is an unconscious process in day-to-day life when projects, things, or people, unwittingly switch from being a desire to an attachment, especially when it is brought into our sphere of influence.

It is important to realise, that nothing is truly ours. We are all, as my favourite Buddhist author, Thich Nhat Hanh says, Interbeing, or interconnected. If we learn to dissolve our sense of self, we will then realise that nothing truly belongs to us. We might be given stewardship for some time, but people don’t belong to us, things don’t belong to us, for after we die, they cannot be taken with us.

Awareness is the first step to letting go.

Once we are aware, we begin to see how silly it is to cling so tightly to the objects of our attachment. And then, our vice-like grip on them begins to loosen.

(Dear Reader, I think I will never forget this because I actually LOVE potato chips and have often entered supermarkets with the sole intention of buying a bag or two. This is the beauty of spiritual metaphors. Indelibly etched into my brain.)

Antidotes

He gave a list of various antidotes from cultivating self-love, being aware of anicca (impermanence), and developing healthy boundaries.

I’ll elaborate on the one that made the most impact to me.

Firstly, he said we need to cultivate independence.

We did a little role-playing. He told us to ask him, “Bhante, are you worried about your business projects?”

Seated in the first row, I gamely asked him, “Bhante are you worried about your business projects?”

He smiled and said enthusiastically, “No, because I have no business projects!”

A chorus of laughter.

Then, he told me to ask him, “Bhante are you worried about your dog?”

Grinning, I asked, “Bhante are you worried about your dog?”

Chuckling, he said, “No, because I have no dog!”

And we went on, until he quipped at the end of this exchange, “The person who has nothing, worries about absolutely nothing.”

The room roared with laughter at his pun that hit so unexpectedly close to the bone.

But responding compassionately to a question, he wisely pointed out that instead of losing our houses, relationships and children, when we let go, we actually don’t lose anything at all. We upgrade our house and our relationships. For they are now free.

It is not my home, it is a home I am grateful to be living in.

It is not my children, they are children I have the privilege of caring for, and when they grow up, they are not mine, they lead their own lives and I can be their kalyanamitta (spiritual friend).

Next, he reminded us of the importance of developing self-love so as not to seek validation from others.

Q&A

After the main talk was over, he took questions in a short question-and-answer session.

My hand shot up and I asked him how we should balance the tension between working on projects, and being lazy by “letting them go”.

His answer was wise and blew my mind.

We need to let go of expectations of how our projects will turn out, but if the projects are good projects, we should definitely put our heart into it.

How does one know if one’s working on something good?

Glad you asked.

Projects that brought about monetary benefit were alright for they provided for oneself and one’s family, and can be donated for the propagation of the dhamma.

Perhaps your regular day job as an administrative staff, or a carpenter is like that. It brings monetary benefit for you, allows you to support your family, and allows you to periodically offer dana to sangha members.

He continued by explaining that projects that bring about monetary benefit, and benefits others, that was even better. For it helped others. An example of this would be your job as a nurse, an educator, or a civil servant. It not only provides a monthly income for daily living, but also allows you to benefit your patient, your student, or the general public. That is even better.

Finally, he said that projects that bring about monetary benefits, benefits others, and brings about spiritual growth. Ah, those were the best projects to participate in.

Perhaps you are inclined to write an innovative book about the dhamma after hours of poring over scripture or code a mobile phone app dedicated to the propagation of the Dhamma for a small profit, and giving a percentage of the proceeds to your favourite temple. In this way, not only do you manage to earn a living, if you are a writer or a software engineer, it benefits others, and also brings about spiritual growth for yourself and others.

I thanked him for his answer and was most grateful.

Conclusion

I am most grateful to the Singapore Buddhist Mission for organising this talk by Bhante Āyasmā Rāhula and look forward to attending future dhamma-sharing sessions there.