*SPOILER ALERT!*

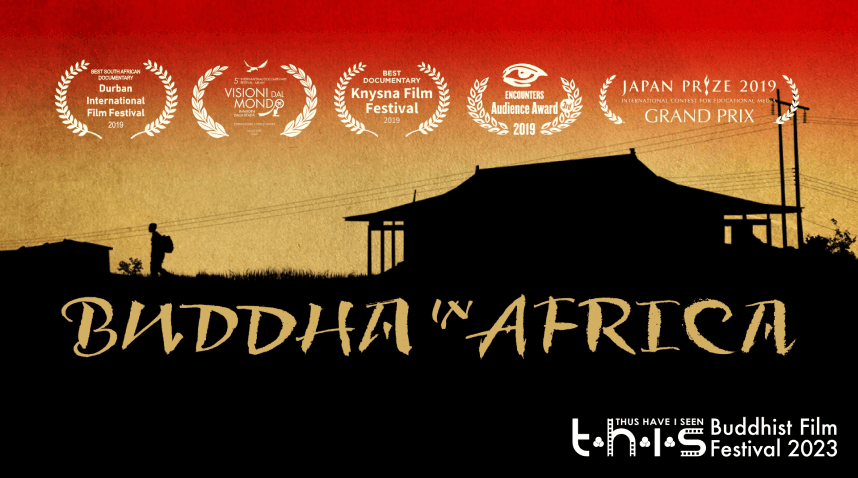

Buddha in Africa by Nicole Schafer introduces us to the story of Enock Bello, a Malawian orphan living in a Chinese Buddhist orphanage. We learn who he is, but more importantly, where he is, both in his trajectory of life and amongst the wider scope of society. Through the director’s thorough observations and sensitive framing, we get a fuller sense of his dilemma—and the larger powers that influence his choice—as he decides on his path for the future.

At first glance, the documentary seems the ideal form to tackle issues concerning such imbalances of power. The idea is that the very act of training your lens upon a previously underseen subject helps redress some of that imbalance. Buddha in Africa achieves that, at least.

However, with a subject like this, there is a second set of power dynamics to be considered—that between the subject and the documentarian.

Who, really, is in charge of this story, the one being gazed at or the one doing the gazing? The film neglects some of these blind spots, though that doesn’t necessarily negate what value it does offer.

Primarily, Buddha in Africa gives us a glimpse into the workings of an Amitofo Care Centre (ACC) in Malawi. This orphanage takes in kids from the villages and gives them shelter, food, healthcare, and even opportunities to study abroad for their higher education.

The trade-off, of course, is that you have to abide by their rules—these include attending early-morning Buddhist sermons, receiving punishment if you’re late, learning Mandarin, and undergoing kungfu training.

Cultural Imperialism Cloaked as Charity?

From the get-go, it’s clear that the documentary takes a critical position towards what is essentially a form of cultural imperialism. During one sermon, there is a telling shot: a young kid, still yawning, has his hands loosely clasped together in an approximation of the praying gesture. An older teen reaches down to unfurl his fingers, and straighten his palms.

We see many such scenes: most of the kids are made to go through the motions, rather than having any proper engagement with what is being conveyed to them. The younger orphans often cry about wanting to go home. Enock mentions how he doesn’t like the Chinese name they thrust upon him.

Who can blame them? This is an unfamiliar culture, language, and religion. Is the point to improve their access to opportunities and equip them with life skills, or is it simply to engender the expansion of Chinese culture?

Even so, for a Buddhist care centre, there is little delving into Buddhist teachings—at least, not that the documentary has chosen to show. Instead, we get a sense that the institution has two main goals—to help break the cycle of poverty in African nations, yes, but also to bolster Chinese soft power.

And for both, one thing is vital: money. It wouldn’t be unfair to say that at its core the ACC is a commercial enterprise—or, at least, it has to be run like one. Master Hui Li is portrayed to be more of a shrewd businessman than a benevolent monastic, frequently reminding the staff and students of their duty to the patrons. But these are necessary considerations—aren’t they? That is one of the central questions of the documentary.

Poverty Porn as a Money-Making Enterprise?

At some points, this relationship borders on exploitation. We see the orphans preparing for a show—a mixture of martial arts feats and tear-jerking drama—that will tour several countries. The purpose, Master Hui Li reminds Xiao Bei, the kungfu coach, is to garner audience sympathy and convey the orphans’ gratitude towards their donors.

During the rehearsals, Xiao Bei guides the boys through the right motions, and more crucially, the right emotions. In one scene of their performance, Enock and another orphan act as an ill mother and her child. They stagger onstage in ragged clothes, weak, and starving.

There are projected photos of barren scenery and stick-thin babies, complete with sentimental string music. It is basically dramatised poverty porn.

A voiceover functions as their dialogue, delivering the characters’ lines in Mandarin and English. The actors, however, do not actually speak. They are spoken for in languages that cater to the audience, that aren’t meant to express their own stories or identities.

But the point is that it works. The audience finds all this tremendously moving. After the show, donations come rolling in.

This is a charity that, when framed in this manner, plays into the form of a saviour complex.

In Buddhist terms, pity seems to be the driving force here, rather than compassion: a separation still exists between the self (the donors) and the Other (their beneficiaries), who are seen only as “victims” below the donors’ standing.

Malawi is subsumed into the generic concept of some abstract “Africa”, and its cultures and ways of living are depicted to be in opposition to civilisation and advancement. Still, despite the presence of the documentarian’s camera, the ACC staff are not at all self-conscious about what they’re doing or the ways in which it may be problematic.

This, more than anything, reveals their sincere belief in the inherent righteousness of their mission.

Thus, a more charitable interpretation becomes possible—that ultimately, this is all done to improve the welfare of the orphans, and indeed, the socioeconomic conditions of Malawi.

If a little cultural imperialism is involved, well, it’s just a practical prerequisite to elicit donor support—how else would they pay for the facilities and resources required to bring up healthy children? Perhaps it is capitalism that lies at the root, not cultural superiority. It’s hard to tell if that is better or worse.

Asian parenting for a Malawian Boy?

I’ve been speaking in broad strokes, but Schafer also tactfully leaves room for grey areas. The ACC staff, when they painstakingly advise the orphans on their future paths, may come off as condescending.

But we see there is also genuine concern, in keeping with the stereotypical Asian style of parenting—plan your child’s future on their behalf, because they don’t always know what’s good for them!

At the same time, they acknowledge that these kids have to make their own choices.

Enock has to choose: stay on in Malawi with his family or study abroad in Taiwan. Initially, he opts for the former. When he gets back to the village, however, it is his grandmother and aunt who gently chide him for this decision, stating how they won’t be able to support him, how they may need to rely on him in the future.

The adults, whether from ACC or his family, are in agreement here: the wiser choice is to study in Taiwan, as this affords him more access, knowledge, and networks. They are not wrong. Neither is Enock in wanting to stay. Life is full of impossible riddles.

Impossible Choices in Impossible Circumstances

Another impossible riddle: how may children be introduced into a religion?

It is hard for a child to make a fully informed decision, much less one as complex as choosing which religion to follow—not simply because they lack the life experience, but also because they are always in positions of lesser power in relation to the adults in their lives.

We see that no religion is above compulsion or indoctrination. After all, proselytization is a religion’s way of reproducing and surviving, as inherent as DNA. But this is not unique to ACC. Aren’t most religions passed down like this from parent to child, who may not have any real say in the matter? Interestingly, in Buddhism, professing that you are a Buddhist doesn’t make you one. It is the ethics and practice that we uphold that is more important. Buddha did not hold back on the importance of our actions by likening a monk who has weak moral virtues as a donkey proclaiming to be a cow. No amount of proclamation can transform someone.

The orphans are also reminded that they have a choice between staying on or leaving the orphanage. But is a choice possible under such circumstances? Can anyone walk away from a life with better material conditions that are necessary to one’s mental and physical well-being?

The methods by which ACC spreads the Dhamma are therefore questionable, both in their effectiveness and ethicality. Dhammapada Verse 100 states: “Better than a thousand useless words is one useful word, hearing which one attains peace.” ACC’s preaching may take up more than a thousand words, but how many actually reaches the kids? Especially when the staff’s conduct doesn’t necessarily reflect Buddhist principles—the help they offer is only on the condition that you embrace their culture.

Perhaps this is something that every charity organisation needs to constantly reflect upon and grapple with: What conditions or expectations are they imposing (consciously or otherwise) upon the very people they’re proclaiming to help?

The Complex & “Un-Buddhist” Father Figure

The documentary shows us that Enock’s relationships with these adults are therefore multifaceted and complex. His bond with Xiao Bei in particular provides a few wholesome moments. They recall fond memories and share photographs from previous travels. Xiao Bei worries about Enock’s future and is even accepting of the fact that Enock still holds on to Muslim beliefs (as it’s the religion of Enock’s family).

It is apparent that the coach has become a father figure to Enock, a role both have embraced. Despite everything, they have found a human connection in this world. This coach who understands Enock the most, however, is also later charged with assault, after another student’s refusal to be punished escalates into an armed fight. Xiao Bei is then deported.

Enock accepts this. He points out the hypocrisy: Buddhism is about maintaining a calm mind, not acting out of impulse. Xiao Bei’s behaviour is the opposite of that.

Home Is Always Elusive

The documentary raises another personal question: What is home? To Enock, despite being brought to ACC at 6, home is still the village where his grandmother lives. But he is something of an outcast there—his friends don’t recognise who he’s become and he can barely speak Yao.

Can a place you return to once a year still be your “home”? But isn’t that the case, too, for many of us? It is never about how much time is spent there.

In a profound scene, Enock begins crying after looking at a photograph of his parents. Despite a lifetime without his parents, the grief is still there. Connections like these are hard to explain. Sometimes, home is its own absence.

Are These Emotions Manufactured?

When it comes to documenting such intensely personal moments, Buddha in Africa might border on the voyeuristic—is a real person’s emotion being put on display as spectacle? At times, Enock shows awareness of the documentarian’s presence, sharing his thoughts directly to the camera.

Mostly, however, the camera simply observes. In her director’s note, Schafer mentions how “it took quite awhile for me […] to get through to the real Enock”. We also find out that that touching moment where Enock sees the photograph of his parents is, to an extent, engineered—Schafer had initiated “this process of reflection into his past” when she found out how little he knew about his parents.

Admittedly, her treatment of the subject is tender and thoughtful, but the question remains: What are the boundaries of a documentarian’s role in capturing an insightful story? It might be more honest if the documentary itself has been more transparent about this process of involvement, recognising how it has influenced the subject’s development, rather than effacing the director’s role in materialising certain narratives.

The Trap and Dependency on Foreign Systems

What, then, is the documentary’s final message? The director, in another interview, said, “I suppose it’s just this idea that the key to the future of the continent’s development is always held by outsiders, and that in order to succeed, we always have to adapt to foreign value systems and policies. I think Enock’s story challenges this idea in very refreshing ways.”

But although Schafer does give us a nuanced and incisive portrait of this issue, Enock’s ending, or at least the ending the documentary has opted for, doesn’t challenge this idea, only reinforces it.

Any agency he has expressed through his initial decision is diminished by the end, where the circumstances of his life drive him down a path he hadn’t wished to take.

Schafer also spoke of how she wanted to explore Enock’s story as being emblematic of the wider political relations between China and the African continent. I think that’s the main problem in this approach—it comes across as a purely academic interest, reducing a real person into a symbolic subject, a microcosm that serves only as a metaphor.

The documentary successfully captures a complex, thought-provoking story, and is well worth watching for that. But my mind keeps returning to the moments where Enock is shown staring out one window or another, lost in unexpressed thought, silent. One can only hope the next time we hear his story again, it will be in his own words, with an ending he’s chosen for himself.