TLDR: Inside Out 2 brilliantly showcases Dhamma concepts like the sense of self, the five aggregates, and the Three Marks of Existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self. Did you catch these themes in the movie?

Writer’s Notes: Huge thank you to Claire, Yean Khai, and various DAYWA friends who shared their post-movie reflections with me, which were collated to create this meaningful piece for our readers. 🙂

The animated film “Inside Out 2” offers rich insights that resonate deeply with core Buddhist teachings. As we follow Riley’s journey through adolescence, we witness a clear illustration of fundamental Dhamma principles, particularly the Three Marks of Existence: Anicca (impermanence), Dukkha (suffering), and Anatta (non-self).

The Fabrication of Self

Central to the film is the concept of a constructed self, mirroring the Buddhist understanding of identity as a mental fabrication.

Riley’s sense of self evolves through her experiences, beliefs, and memories, represented by the “islands” in her mind. This evolution parallels the Dhamma teaching of dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda), where our identity is seen as a product of interconnected conditions.

The movie highlights how our memories are coloured by associated emotions as seen by the various colours of the memory orbs, often distorting our perception of past events. Riley’s reflections show that her self-concept is built from these emotionally charged memories, echoing the Buddhist teaching that our sense of self lacks a permanent essence (anatta).

As Riley’s sense of self develops, it becomes more complex, mirroring the intricate nature of human existence. Her indecision between thoughts like “I’m a good person” and “I’m not good enough” reflects the instability of a self-concept rooted in fluctuating conditions.

This highlights the Dhamma teaching that a stable, positive sense of self is beneficial for navigating the conventional world but ultimately impermanent and subject to change.

The moment one clings to a permanent and unchanging identity, they ultimately suffer. Changes in mind states & the physical body result in different needs for adjustment. If one rejects the flow of change, they too will suffer.

The Role of Emotions

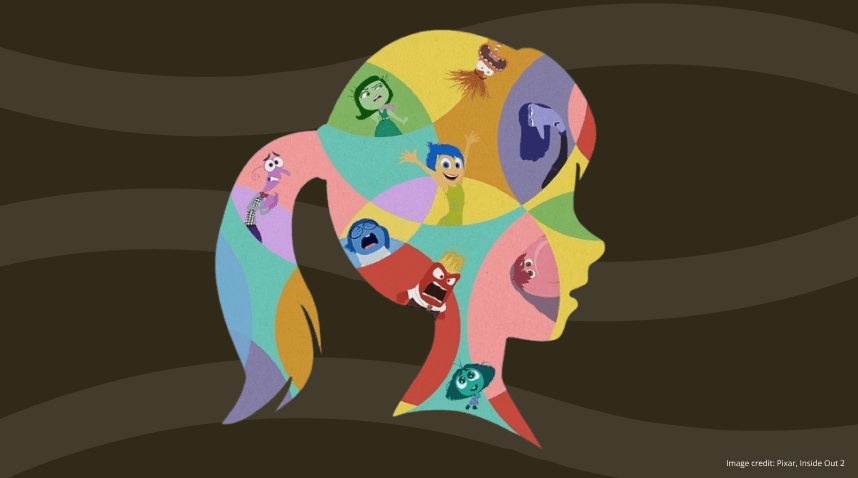

“Inside Out 2” beautifully illustrates the complex interplay of emotions within the mind. Each emotion – joy, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust – plays a crucial role in Riley’s life, shaping her responses and actions.

This aligns with the Buddhist understanding of emotions as part of the five aggregates (pañcakkhandhā) that constitute a person: form, feeling, perception, mental formations, and consciousness.

The film emphasises the importance of embracing all emotions rather than selectively choosing them to define oneself. This resonates with the Dhamma view that all experiences, whether pleasant or unpleasant, are valuable for spiritual growth and understanding the true nature of reality.

This reminds me of a story shared by Ajahn Brahm in his book Opening Up to Kindfulness, where he explains how we can make the most out of negative experiences in our lives:

“Whenever you tread in the dog poo, never wipe it off your feet but always take it back to your house and dig it under your mango tree. One year later, your mangoes will be sweeter than before. But when you taste that mango, you must remember that what you’re tasting is dog poo transformed.”

When you understand this simile, all of that poo from your life, all of the terrible things you’ve done or which have been done to you, they are just fertilisers or opportunities for growth. It makes mangoes, or your life, sweeter.

So don’t get negative but give it metta, and the next time anything terrible happens to you, you can say, ‘Whoopee! More fertiliser for my mango tree!’”

This story beautifully illustrates how negative experiences can be transformed into positive growth. So the next time we feel angry or sad, perhaps, we can try to reframe our attitude towards the situation and make it beneficial for our character building.

In “Inside Out 2,” another interesting point to note is how specific emotions are given nuanced roles. Anxiety, for instance, represents Riley’s fear of the unknown future, while fear relates to the uncomfortable anticipation and uncertainty of current and past events.

These emotions serve as protective mechanisms, illustrating how our mental states arise due to specific causes and conditions. This aligns with the Buddhist sayings of dealing with anger, changing our perspectives from ‘I am angry’ to ‘There is anger’. This gives one the space to see emotions from a distanced view and understand them as not something to be taken personally.

The Three Marks of Existence

1. Anicca (Impermanence): Throughout the film, we see change as the only constant in Riley’s life. Her external environment shifts as she grows, but more profoundly, we observe internal changes in the complexity and intensity of her emotions, her core values, and her sense of self.

2. Dukkha (Suffering): Riley’s struggles with desires and cravings form a poignant portrayal of Dukkha. Her yearning for acceptance, success in ice hockey, and friendships often lead her towards Akusala (unskillful) thoughts, speech, and actions. These, in turn, cause her mental turmoil and suffering, demonstrating how our attachments and aversions can be the root of our discontent.

3. Anatta (Non-self): The film’s depiction of Riley’s mind, with its various emotions and impulses vying for control, clearly illustrates that there isn’t a single, unified “self” running the show. Instead, we see a complex interplay of aggregates, much as Buddhist psychology describes.

Universal Nature of Mental Processes

Another personal favourite part of the movie was how Riley’s parents were also shown to be governed by their emotions. This was clearly depicted in the puberty alarm scene when Riley was throwing a tantrum in the morning, saying she wasn’t prepared to go to camp and felt gross. Her mum initially entered the room sounding angry because Riley wasn’t packed.

However, upon observing Riley’s flustered and emotional state, her mum’s emotions – particularly Sadness – guided all emotions to “stick to the prepared script” she had for dealing with Riley’s emotional behaviours due to puberty.

This allowed her mom to remain composed and speak to Riley calmly, without letting any single emotion overtake her behaviour. (Here’s the movie’s snippet if you need a recap!)

This scene reminds us that everyone is subject to the same mental processes. It’s important to note that our parents, loved ones, colleagues, friends and basically everyone we interact with in life don’t always have a “prepared script” to deal with various situations, and are also controlled by our emotions.

Recognising this can foster empathy and compassion, as we understand that others are also influenced by their emotions and conditioning. This aligns with the Buddhist practices of loving-kindness and compassion.

As explained by Ajahn Amaro brilliantly in this video, having loving-kindness is not about “liking” everything, or “trying to think pink or have a positive attitude” towards every being, but to have kindness and open-heartedness to others, even when we may not like the actions or speech said by others.

We can still practise remaining kind and open-hearted to the person, in this case remembering that they are ultimately just like ourselves, governed by the same universal mental processes.

The Mountain of Kamma

The scene where Riley’s bad memories flood back serves as a wake-up call, both for her and for us as viewers. The huge mountain of memory orbs from Riley’s life thus far reminds us of the Buddhist understanding that we are the product of our kamma (volitional actions), our conditioning, and our experiences – both good and bad. As the Buddha taught:

“I am the owner of my Kamma, heir to my Kamma, born of my Kamma, related through my Kamma, and live dependent on my Kamma.”

Watching the movie reminds me that a balanced, aware approach to our inner world is crucial for personal growth. From a Buddhist perspective, this awareness is a step towards achieving the state of a sotapanna (stream-enterer) – one who has abandoned the fetter of identity view and has glimpsed the impermanent, unsatisfactory, and non-self nature of all phenomena.

Conclusion

“Inside Out 2” serves as a powerful metaphor for core Dhamma teachings. It reminds us of the ever-changing nature of our experiences, the potential for suffering inherent in our cravings, and the complex, interdependent processes that we conventionally call our “self.”

By reflecting on these themes, we can deepen our understanding of the Dhamma. We learn to see beyond our fabricated sense of self and recognise the impermanent and conditioned nature of all phenomena.

This understanding can lead us to navigate life’s challenges with greater wisdom and compassion, moving us closer to true peace and liberation.

In essence, “Inside Out 2” not only entertains but also enlightens, offering viewers a unique opportunity to contemplate profound Buddhist truths through the lens of a colourful animated world. It encourages us to embrace all aspects of our emotional life while cultivating a deeper awareness of the true nature of our existence.

BONUS iykyk: Perhaps in an alternate universe where Riley is a sotapanna in a movie called Outside In, you will see her sense of self disappearing in a vibrant electric spark ⚡️. And that will certainly shorten or perhaps put an end once and for all to all sequels of the movie.

Wise Steps:

- Be mindful of how our emotions arise in different circumstances, recognising them as protective mechanisms that arise due to specific causes and conditions.

- Cultivate understanding and compassion towards others, especially when we disagree with their viewpoints, by acknowledging the diverse emotions they experience and the different conditions they have encountered in their past.

- Remember that our sense of self is composed of various causes and conditions and is subject to change. Therefore, we can continuously put in the right and wholesome conditions to become better people every day!